Today we have a host of checklists, regulations, and safety measures that prevent incidents from happening or getting out of hand. We’re fortunate that air travel is the safest form of transportation, but just a few decades ago, the world was much different. Authorities had only recently implemented radar for critical cities and started designating airways for navigation and traffic. Unfortunately, on June 30, 1956, these would not be enough to prevent a mid-air collision over one of America’s most remarkable natural landscapes.

A busy morning at LAX

Many passengers were waiting to board their flights at Los Angeles International Airport on the fateful summer morning. In the years following World War II, the United States and much of the world experienced an economic boom, so more people than ever could afford to fly. Among the flights leaving LAX that day were Trans World Airlines Flight 2 and United Air Lines Flight 718.

TWA Flight 2, flown by a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation, underwent minor maintenance that morning but was cleared without concern. The aircraft, flown by captain Jack Gandy, first officer James Ritner, and flight engineer Forrest Breyfogle, would take 64 passengers from Los Angeles to Kansas City. Captain Gandy was a well-experienced pilot with over 15,000 hours and had flown this route nearly 200 times; it was shaping up to be a typical day as the aircraft departed LAX at 9:01.

Three minutes later, because of a schedule delay, United Air Lines Flight 718 received clearance and took off at 9:04, bound for Newark via Chicago and Philadelphia. With his 17,000 flight hours, Captain Robert Shirley, accompanied by first officer Robert Harms and flight engineer Gerard Fiore, made himself comfortable in the Douglas DC-7 nicknamed “Mainliner Vancouver.”

Their paths would cross about an hour and a half into the flights

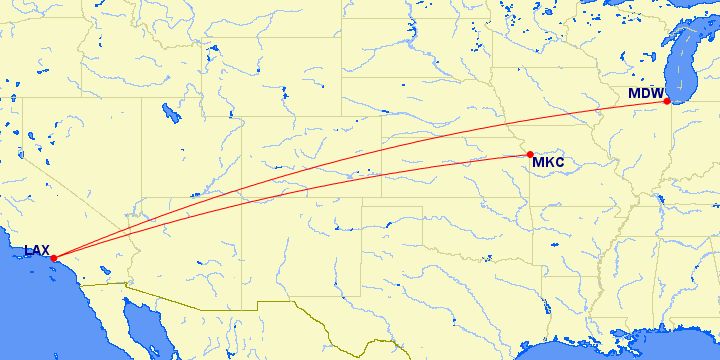

Initially, the two aircraft took off in separate directions, TWA 2 heading northeast towards waypoint Daggett and UAL 718 directly east to Palm Springs and then slightly north towards Needles. However, the TWA aircraft would head for waypoint Trinidad near the Colorado and New Mexico border, flying more directly east than earlier. At the same time, the United flight was to fly over Durango, also along the same border but much more western, and as a result, continuing along the northeast heading.

However, the directions each aircraft had to follow, after departing just a couple minutes apart, would force them to cross directly over Grand Canyon National Park. In 1956, aircraft didn’t communicate directly with controllers while flying but through company radio operators who would relay messages. This system would become vital as, at 9:21, TWA Flight 2 approached Daggett and asked to climb to 21,000 feet.

After a quick game of telephone between all involved, the controllers between LA and Salt Lake City denied this request. The controllers noticed that TWA 2 would cross paths with UAL 718, already flying at 21,000 feet, and knew they would collide if approved. TWA’s operator then asked if they could receive clearance for “1,000 on top,” meaning 1,000 feet above the clouds, which was subsequently approved.

By flying on top of the clouds, the aircraft would switch to VFR or Visual Flight Rules, and the pilot would be responsible for their navigation and separation from other aircraft. The controller that approved this climb to “1,000 feet on top” hadn’t realized that, over the Grand Canyon that morning, clouds had reached 20,000 feet. Although this clearance allowed Captain Gandy to fly at any height at or above 21,000 feet, he essentially received permission for the same flight denied minutes prior. Operators did relay the information about UAL 718 in the area at 21,000 to Captain Gandy, who reported he understood.

Critical waypoints reached close to the Grand Canyon

At 9:58, United 718 passed over Needles and reported that, at around 10:31, they could cross the Painted Desert Line, a 173-mile-long line between Utah and Arizona used by air traffic to provide info about where a flight was in the uncontrolled airspace. A minute later, TWA 2 reported in, making a similar estimation. The controllers knew that two aircraft would likely fly at 21,000 feet, crossing the Painted Desert Line simultaneously. However, since it could be anywhere along the path, and they were in uncontrolled airspace, the responsibility to avoid collision fell into the hands of all the involved pilots.

If you're into aviation history, you can read more with Simple Flying here.

Data shows that, for unconfirmed reasons, both planes took a more northern path than what their original flight plans said to do. Many believe this is due to thunderstorms in the area to the south, which the pilots may have avoided to give passengers a scenic view of Grand Canyon National Park. Unfortunately, in their attempts to avoid these storms, each pilot made a series of turns, ultimately putting them on a collision course. And because of the tall, dark clouds, the pilots likely couldn’t see each other in an area where they were responsible for avoiding each other.

Tragedy strikes

At about 10:30, at 21,000 feet over the Grand Canyon, the Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation and Douglas DC-7 collided. Both aircraft tumbled downwards, and upon crashing in the Grand Canyon, 128 lives perished. The probable cause, as written in the final report, is extensive and as follows:

“The pilots did not see each other in time to avoid the collision. It is not possible to determine why the pilots did not see each other, but the evidence suggests that it resulted from any one or a combination of the following factors: Intervening clouds reducing time for visual separation, visual limitations due to cockpit visibility, and preoccupation with normal cockpit duties, preoccupation with matters unrelated to cockpit duties such as attempting to provide the passengers with a more scenic view of the Grand Canyon area, physiological limits to human vision reducing the time opportunity to see and avoid the other aircraft, or insufficiency of en-route air traffic advisory information due to inadequacy of facilities and lack of personnel in air traffic control.”

In the wake of one of the worst aviation disasters, the US Congress passed the Federal Aviation Act, which included the establishment of the Federal Aviation Administration. This independent agency would oversee all commercial and military flights, build a modern air traffic control system, and enhance flight traffic rules. For the better, aviation would never be the same again.

What air accidents are you interested to know more about? Let us know in the comments below.

Sources: The Final Report, ASN, grcahistory, Medium