The A340 was a significant development at the time of its launch. It marked Airbus' entry into the quad jet market and offered healthy competition for other manufacturers.

Production of the A340 ended in 2011, but it remains in service with several airlines. It has been a big casualty of the slowdown in 2020, though, with retirements increasing.

This guide takes a look through the history and development of the A340. Four variants were developed, and it was designed alongside the twin-engine A330. This was a smart move by Airbus, lowering costs, and covering the fact that the A340 soon fell out of favor as twins improved.

[powerkit_toc title="Table of Contents" depth="2" min_count="4" min_characters="1000"]

Development of the A340

Airbus and the A300 project

The story of the A340 starts with the A300 and A320. The A300 was Airbus' first aircraft, in 1972. It was a twin-engine, twin-aisle aircraft, with a shortened variant, the A310.

Following initial success with this, Airbus went on in the early 1980s to create a new twin-engine, single-aisle aircraft. There was a gap in the market here, with the US manufactured Boeing 737 dominating and no European alternative. European governments realized this and worked with manufacturers on several proposals for a new, European constructed, competitor. Airbus eventually won and went on to develop the A320 family.

With the A320 project launched, and on the way to delivery, Airbus started to look at the market for larger, widebody aircraft. Again, there was an opportunity to compete with Boeing in this area, especially with the 747 starting to sell well.

A big question, however, was whether to develop a twin-engine or a four-engine (quadjet) widebody. We know now that ETOPS ratings have made twin engines much more desirable. But at the time, there were still severe restrictions on how far twin-engine aircraft could fly from diversion airports, limiting their use for many airlines.

Airbus' vice president for strategic planning, Adam Brown, explained his views on this (in reporting by FlightGlobal):

"There was much internal debate whether to go with the big twin or the quad… North American operators were clearly in favor of a twin, while the Asians wanted a quad. In Europe, opinion was split between the two…The majority of potential customers were in favor of a quad despite the fact, in certain conditions, it is more costly to operate than a twin -they liked that it could be ferried with one engine out, and could 'fly anywhere' – remember ETOPS hadn't begun then."

The solution was to develop two aircraft: a twinjet, and a quadjet. This would meet the needs of both sets of customers, and there would be savings by developing both aircraft together.

The resulting project looked at the development of two aircraft:

- The TA9, twin-engine, would have a range of 6,100 kilometers (3,300 nautical miles)

- And the TA11, four-engine, would have a range up to 12,650 kilometers (6,830 nautical miles)

Developed alongside the A330

In 1986, the development project moved forward and became the A330 and A340. Airbus board-chairman Franz Josef Strauß said at the time:

"Airbus Industrie is now in a position to finalize the detailed technical definition of the TA9, which is now officially designated the A330, and the TA11, now called the A340, with potential launch customer airlines, and to discuss with them the terms and conditions for launch commitments."

Developing the two aircraft together brought many advantages. They shared the same basic fuselage and wing design, and many structural components and systems, as well as a common flight deck. This, of course, saved money in the development and brought the aircraft to market faster than if they were designed separately.

Airbus also made further savings by using designs from the A300 and A320. The fuselage of the A330/A340 is based on a stretched A300 fuselage. And the fly-by-wire controls and cockpit are inherited from the A320.

The main differences between the A330 and A340 are, of course, in the two or four-engine setup. The A340 also has a larger wing and an additional middle rear landing gear. This middle landing gear is unusual; most heavy aircraft use two gears with increased wheels to cope with the extra load.

The A340 does have higher capacity variants (the A340-500 and -600) than the A330, and also offers a greater range. But there are variants of each series that come close. Simple Flying took a more in-depth look at the differences between the two aircraft previously.

This similarity in capacity and range is apparent if you consider the A330 and A340 family together (listed by increased typical capacity):

- A330-200 can carry 246 passengers in two classes to a range of 7,250 nautical miles.

- A340-500 can carry 293 passengers in three classes to a range of 9,000 nautical miles.

- A330-300 can carry 300 passengers in two classes to a range of 6,350 nautical miles

- A340-200 can carry 303 passengers in two classes to a range of 7,600 nautical miles.

- A340-300, 335 passengers in two classes to 7,150 nautical miles.

- A340-600, 380 passengers in three classes to a range of 7,550 nautical miles.

Getting around ETOPS restrictions

The main selling point of the A340 was its four engines, not necessarily its increased capacity or range. Airbus would return later to the high capacity model later with the A380.

Having four engines enabled it to operate longer over-water flights, something for which the A330 was restricted. ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards) were introduced in the early 1980s, to reflect the increasing safety and performance of twin-engine aircraft and allow them to fly further from a diversion airport. The first rating was given, in 1985, to Trans World Airlines flying a 767. This allowed it to fly 120 minutes from a diversion airport.

Before this, twin engines were restricted to flying 60 minutes from a diversion airport. The first (pre-ETOPS) extension to this was given to the A300, with a limit of 90 minutes.

These ETOPS regulations did not restrict the A340 quadjet. This gave airlines the choice of the A330 or A340, depending on planned operations and fleet size.

Production, testing, and entry into service

The A330 and A340 program was launched in June 1987, just before that year's Paris Air Show. At the time, there were 130 orders from 10 airlines.

Aérospatiale constructed a new assembly facility at Colomiers, near Toulouse, France. This made extensive use of robotics and automation, another cost-saving move by Airbus. There were similar investments into production facilities in the UK by BAe, with a technical center at Filton and expansion of its wing production site at Broughton.

The A340 took its first flight on October 21st, 1991. During testing, problems were discovered with some warping of the wings at cruising speed, and changes had to be made to the underwing to add stiffness. European certification was achieved in December 1992, with the US FAA certification following in May 1993.

The first aircraft was delivered to launch customer Lufthansa on February 2nd, 1993, and it began service on March 15th.

A340 variants

There are four variants of the A340, two offered at launch, and two later.

A340-200

The A340-200 is one of two initial variants, offered at launch in 1987. It is the shortest variant of the series, offering a typical two-class capacity of 303 (less for three-class).

Both this and the -300 variant use CFM International CFM56-5C engines, providing thrust of 31,200–34,000 lbf. These were upgraded for later variants.

Only 28 of this variant were ordered, with the slightly larger A340-300 proving much more popular.

A340-300

The A340-300 was also offered at launch. It was the first aircraft to be delivered to Lufthansa in 1993. It is stretched just over four meters from the A340-200, which increases the typical capacity from 303 to 335.

Of the two launch variants, this was by far the most popular, with 218 delivered. It was also developed into an enhanced model, the A340-300E, with improved engines (the same type) and upgraded avionics and cockpit systems (part of the development for the next two A340 variants).

A340-500

The A340-500 and -600 variants were developed in the late 1990s as higher capacity and increased range upgrades to the original two variants. They first flew in 2001 (the-600) and 2002 (the -500).

The A340-500 was launched in March 2003 by Emirates, after the original launch customer, Air Canada, filed for bankruptcy.

The -500 is stretched just over four meters from the -300. The focus, though, is not on increasing capacity but on expanding its range. It offers a similar capacity to the -300, but the range is increased to an impressive 16,670 kilometers (9,000 nautical miles).

This was the highest range of any aircraft until beaten by the A350ULR. Singapore Airlines used the A340-500 for its Singapore to Newark service (now operated by the A350-900ULR).

The engines were switched to Rolls-Royce for these variants, offering significantly higher thrust. The -500 uses Trent 553 engines, and the -600 uses Trent 556 engines.

A340-600

The focus of the A340-600 was on capacity. It offers a similar passenger capacity to the Boeing 747 but adds additional cargo space. Virgin Atlantic was the launch customer in August 2002.

It is stretched 12 meters over the -300, giving a typical capacity of 380 (but with a maximum exit limit of 440). It was the longest aircraft in service (beating both the A380 and the Boeing 747-400) until the launch of the 747-8.

Like the larger -300 variant, the -600 has been much more popular than the -500. Airbus delivered 97 aircraft, as opposed to just 32 -500 aircraft.

What about the A340-400?

The obvious variant missing is the A340-400. Why does the numbering skip from -300 to -500? The simple explanation is that Airbus did propose the A340-400 in the 1990s as a stretched version of the -300 (for a discussion of this see airliners.net). It would use the same wing design, avionics, and engines, though, as the -300 and was not popular with airlines. The -500 improved on this and became the option that airlines purchased.

A340 orders and deliveries, and leading operators

Beating the competition

One of the aims of the A340 was to replace aging quadjets, including the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. This was a market Airbus had not yet entered but saw an opportunity to offer a more efficient competitor, using updated technology.

The A340 also got an early boost when problems were found with the McDonnell Douglas MD-11. This trijet widebody first flew in January 1990, slightly before the A340. It soon became apparent, though, that it did not meet expectations for range and fuel efficiency.

This was a problem for several airlines. In particular, Singapore Airlines had hoped to operate it between Singapore and Paris, but this would not be possible. As a result, it switched its order for MD-11 aircraft to A340-300s. Production of the MD-11 ceased in 1998, partly as a result of competition from the A340 (and also the Boeing 767 and 777, with Boeing and McDonnell Douglas merging in 1997).

A340 operating airlines

In all, 377 A340 aircraft have been delivered to 48 airlines.

The largest operators of the A340 have included the following airlines. This is based on orders and deliveries data from Airbus, some airlines have operated more aircraft through leases or second-hand purchases (some of this is noted in the descriptions following).

|

Airline |

A340-200/300 orders |

A340-500/600 orders |

Total orders |

|---|

Lufthansa

Lufthansa has been the largest operator of the A340, ordering 59 aircraft in total, and operating up to 62. It was the launch customer for the A340-200 in 1992, operating eight aircraft and retiring the last in 2006. It also operates A340-300 and A340-600 aircraft.

Nico Buchholz, Senior Vice President Corporate Fleet, Lufthansa, said of the aircraft (as reported by defense-aerospace.com):

"The additional A340-600s enable Lufthansa to underpin its growth in the long-haul sector. Furthermore, the aircraft play an active role in Lufthansa's ecological contribution to lower fuel consumption and reduced noise emissions."

Lufthansa has been a significant Airbus operator, with A300, A310, A320, A330, A340, A350, and A380 orders. This has helped commonality in operations and crew training. It continues with plenty of Airbus aircraft, but the balance is shifting with an order for the Boeing 777X and 787.

While it has not yet retired its A340s, they have fallen out of favor during the slowdown in 2020. As of late May 2020, its entire fleet had been grounded and sent to storage at Teruel graveyard. Future plans see Lufthansa reducing its fleet size, and splitting aircraft between hubs, but is not confirmed what will happen to the A340.

Iberia

Iberia took delivery of the A340-300 in 1996 (which it operated until 2016), and the A340-600 in 2003. It first ordered three of the larger aircraft, intended to replace its aging Boeing 747-300 aircraft.

According to reporting by defense-aerospace.com at the time, the efficiency improvements were a significant factor in this decision, as was the commonality with the A320 and the cost savings that would offer. It went on to operate 18 A340-600s (purchasing 16 and taking two on lease).

Iberia confirmed the retirement of its entire A340 fleet in June 2020. At this point, it had 14 A340-600 remaining in service, with gradual retirement up to 2025 planned.

Virgin Atlantic

Virgin Atlantic has used the A340 extensively for its long-haul flights. It took delivery of its first A340-300 in April 1993, named 'Lady in Red.' It added the A340-600 in August 2002 and was the type's launch customer.

In total, it operated 29 A340s (10 -300s and 19 -600s). They have been in gradual retirement for some time (although one, 'Sleeping Beauty Rejuvenated' made it back from two years of storage in 2018 to rejoin the fleet).

Virgin Atlantic confirmed the retirement of its last three aircraft in April 2020, noting at the time that these three aircraft had flown a combined total of almost 180,000 hours in the sky flying for the airline across more than 21,000 flights.

Singapore Airlines

Singapore Airlines was an interesting customer for the Airbus A340. It had initially ordered the MD-11 but switched this to the A340 when the range of the MD-11 did not hold up in testing. It purchased 17 A340-300 aircraft in 1996, intended for use on long-haul routes that did not need the capacity of the Boeing 747.

The retirement of the A340-300s was also unusual. As explained in a New York Times article in 1999, they were sold to Boeing as part of a deal to introduce the 777.

Singapore Airlines did stick with Airbus to a smaller extent, purchasing five A340-500 aircraft in 2003. These were used for its ultra-long routes to the US until replaced by the A350-900ULR. The last A340 was retired from the fleet in 2013.

Air France

Air France was the joint launch customer, together with fellow European airline Lufthansa, for the A340. It purchased 14 A340-300 in 1993. It has operated 29 A340s, though, since them (according to Planespotters.net). The last A340 was retired in May 2020, earlier than the initially planned timeframe of Q1 2021.

Cathay Pacific

Cathay Pacific was an early adopter of the A340. It leased four A340-200 aircraft in 1994, before ordering the A340-300 from Airbus in 1996. It went on to use the A340-600 as well, again leasing them (it was the first Asian airline to lease the A340-600). In all, it operated 25 A340s over time.

It removed the A340-600 from service in 2009. All aircraft then operated with Hainan Airlines until they were scrapped in 2015.

The A340-300 aircraft, however, remained in the fleet until 2015. Cathay added to its fleet of 11 purchased from Airbus with additional -300s bought from Air China and Singapore Airlines. They regularly operated to London, Vancouver, and Tokyo. The aircraft went into storage into 2015 and were then recycled in the largest recycling project it has undertaken, recycling 90% of the aircraft.

Emirates

Emirates ordered 10 A340-500 aircraft and retired its last A340 in 2016. It also operated eight A340-300 aircraft, not ordered from Airbus.

In earlier times, Emirates had a diverse fleet of Boeing and Airbus aircraft, including the Boeing 727 and 737, and Airbus A300, A310, as well as the A340, but today it has moved to an all A380 and Boeing 777 fleet.

With their early retirement, many of Emirates A340s found further use, including with charter airline HiFly.

Competition and decline of the A340

Improvement in ETOPS ratings

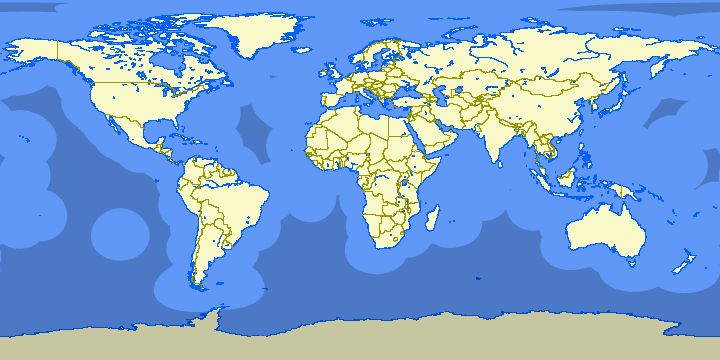

The A340 at the time of its launch was designed to get around restrictions on twin-engine aircraft. With four engines, it could operate further from a diversion airport, importantly including long overwater routes.

In the years that followed, though, restrictions were increasingly lifted on twin-engine aircraft. ETOPS 180 was first given in 1989, and the Boeing 777 became the first aircraft to receive this rating on launch (although in Europe it still had to demonstrate performance at ETOPS 120).

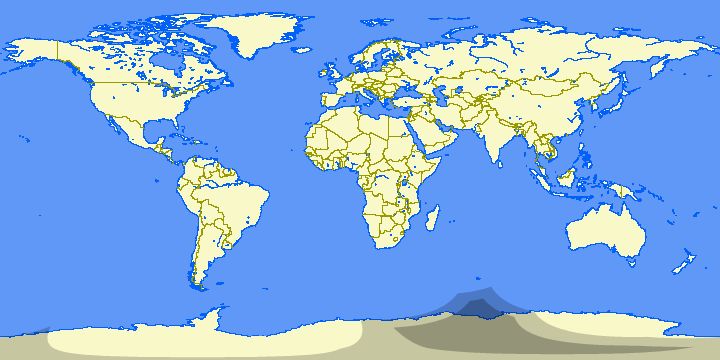

Higher ratings followed. The A330 was rated ETOPS 240 in 2009, and the 777 achieved ETOPS 330. And ratings now go as high as ETOPS 370 for the A350. With limits this high, there are very few restrictions on where the aircraft can operate.

With ratings this high, there are few areas where aircraft cannot operate. With a rating of ETOPS 330/370, the only no-fly area that remains is over Antarctica. This remains a quad-only route, but this had minimal impact on airline routings.

Switching to twin engines

With these improvements, airlines have moved to twin engines. Increasing engine power has helped too. Two engines are cheaper to buy, maintain, and, critically, to operate.

The Boeing 777 soon became the main competitor to the A340. If, of course, offered the efficiency improvement of two engines, but also minimal differences in capacity. The typical seating capacity of the 777-300ER was slightly higher than the A340-600 (332 verses 323). By the mid-2000s, the 777 had come to dominate sales. In 2005, for example, Boeing sold 155 777s compared to Airbus' 15 A340s.

Airbus announced the end of the A340 program in November 2011. Bertrand Grabowski, managing director of the transport group at DVB Bank, summed up the industry views at the time (as reported in The Seattle Times), saying,

"In an environment where the fuel price is high, the A340 has had no chance to compete against similar twin engines, and the current lease rates and values of this aircraft reflect the deep resistance of any airlines to continue operating it."

Aircraft in operation decline

The A340 has been declining in use since the mid-2000s. But the slowdown as a result of COVD-19 in 2020 has seen this increase significantly. As airlines have reduced operations, it is the larger four-engine aircraft that have suffered the most. Many 747 and A380 fleets have gone into storage or been retired early. And the A340 has not fared well.

According to Airbus data for the end of July 2020, only 35 operators of the A340 remained, and only eight of these with a fleet of more than five aircraft. As of July 2020, the ten largest remaining airlines operating it are:

|

Operator |

A340-200/300 |

A340-500/600 |

Total |

|---|

And beyond this, the future does not look good. Amongst the largest operators, Iberia has confirmed it will retire its A340s. And Lufthansa has stored all its aircraft, with their future unclear.

Many retired aircraft have found new homes, though, and, with their relatively young age, they will likely still be flying for some years to come. One of Virgin Atlantic's aircraft, for example, has moved to Nigeria's Azman Air, and thee to Maleth Aero.

And it has even found uses on the ground. Simple Flying reported on a Turkish Airlines A340 converted into a 280 seat restaurant.

Was the A340 a failure?

Given the dramatic decline in A340s and some early retirement of young aircraft (Iberia, for example, has retired its A340s with the youngest just 10 years old), it is tempting to call the A340 a failure. That, however, does not really explain it well.

The A340 was not an unsuccessful aircraft. It served a purpose at the time, but the situation has changed since then. And the fact it was built alongside the A330 (which continues to be in production) means its cost of development was lower, helping justify its more limited sales and use.