We're accustomed to airplanes looking a certain way. Since the era of the Comet, the idea of commercial air travel has been founded on a tube-like structure with wings and a tail. Sometimes those wings are higher or lower, and sometimes the tail is a T or a fin. But fundamentally, airplanes have looked mainly similar for more than seventy years.

Disrupting that idea is something that's been toyed with for some time in a bid to make air travel more efficient. Airbus floated the idea of a blended-wing airplane; others have looked to make wings slimmer or fuselages narrower to improve aerodynamics. But the D8 concept from Aurora Flight Sciences really takes things a step further.

The double bubble

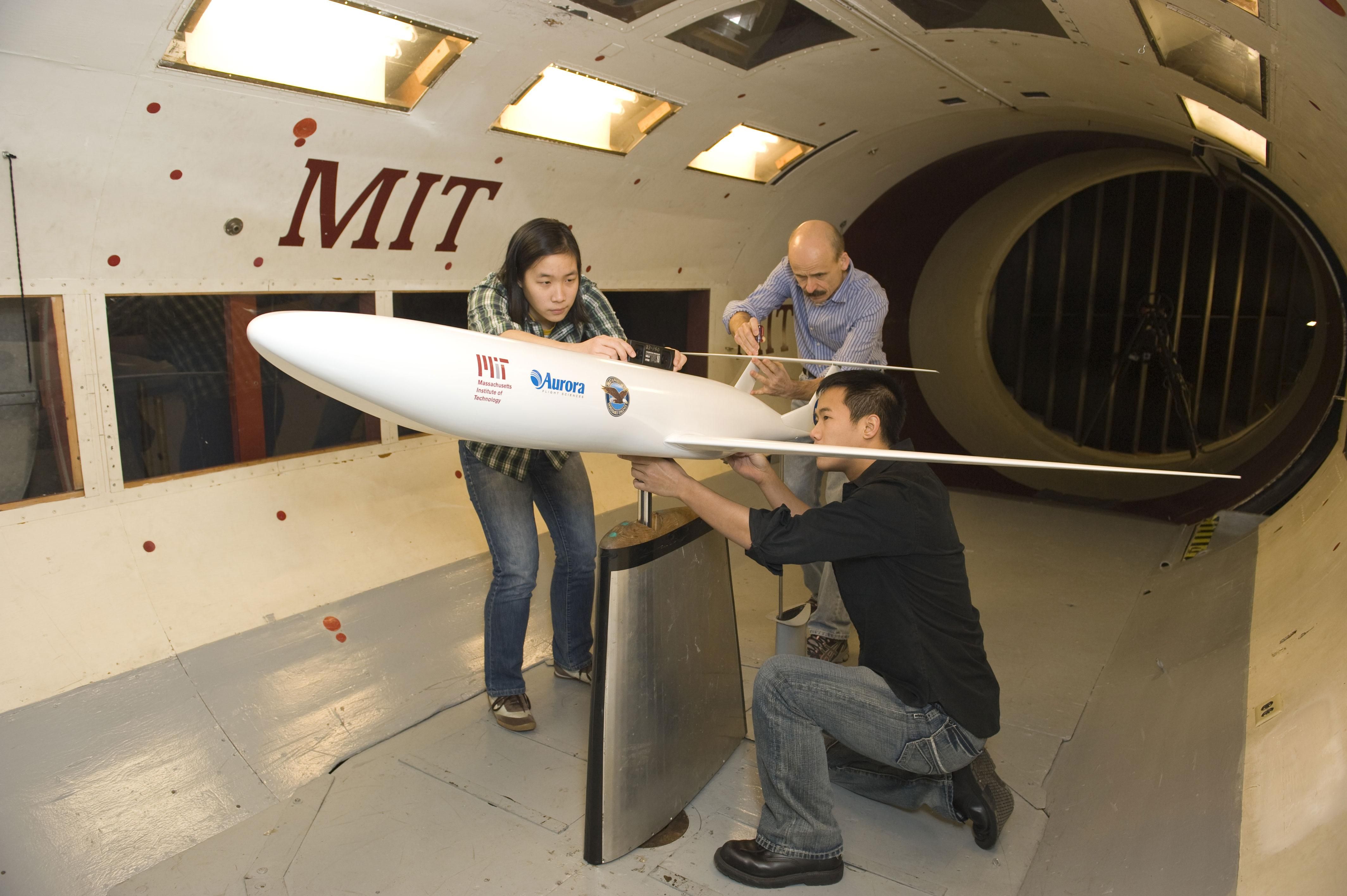

The conceptual design of an environmentally friendly subsonic passenger aircraft was initiated in 2008, when Aurora, MIT and Pratt & Whitney pooled their expertise to develop something new. Funded by a $2.9 million grant from NASA, the team began developing the D8 in mid-2017.

The concept earned the moniker the 'double bubble' due to its unique fuselage design. It is largely based on the Boeing 737, but is essentially a double-width fuselage. It is designed to fly 180 passengers to a range of 3,000 nautical miles; not bad for a short-haul aircraft. With its widebody configuration, turnaround at airports could be faster than current single-aisle aircraft too.

As with many concept aircraft, the D8 was designed to tackle the problem of carbon emissions and noise. By flying at Mach 0.74, developers believed fuel burn would be reduced by as much as 70% and noise by 71 dB compared to a standard Boeing 737-800. However, changes to the design and a desire to fly just as fast as a standard jet, at around Mach 0.82, has driven this down to a 49% fuel burn 40 dB reduction.

What makes the Aurora D8 unique?

The beauty of the Aurora D8 is in its unusual shape. Even at a glance, this is not your average airplane. It has a high aspect ratio wing - a very efficient design feature - and a wide fuselage, providing more natural lift. Added to this, the engines will be designed to be capable of Boundary Layer Ingestion (BLI), reducing friction drag of the fuselage. Positioning the engines at the top of a wide tail and above a flattened fuselage means they should be better able to re-energize the wake.

But that’s where Aurora Flight Sciences has a challenge to overcome. Wake-filling propulsion requires distortion-tolerant fans, if they are to cope with the turbulent air entering the engines. They will also need to be large to take full advantage of the drag reduction effect, and be tolerant of things like debris and ice from the fuselage top potentially entering the powerplants. Nevertheless, wind tunnel testing has shown some encouraging results, suggesting that the BLI of the engines could improve efficiency by 8 - 10% compared to standard airplane designs.

Get the latest aviation news straight to your inbox: Sign up for our newsletters today.

Will we ever see the D8 fly?

The likelihood of the Aurora D8 actually making it to production is higher than some of the concepts that have floated through aviation in the past. For a start, in November 2017, Boeing completed the purchase of Aurora Flight Sciences. While it remains an independent operating model, the company is now able to benefit from Boeing’s resources and market position.

At around the same time, NASA confirmed funding would continue into the project, and the development of the X-plane experimental model. The XD8 would serve to demonstrate the positive technologies and attributes of the D8 through wind tunnel testing, propulsion technologies and a large-scale structural test model.

Everything has gone a bit quiet since then, but the concept retains some impressive characteristics. It might be that the idea has been shelved for a little while, or perhaps testing is quietly ongoing behind closed doors. Either way, the notion of redesigning what we think of as a typical passenger plane is long overdue, and the D8 could hold some clues to the future of air travel.