Ever want to know how aircraft can make a landing in inclement weather or at night? It’s because the United Kingdom’s Blind Landing Experimental Unit (BLEU) did an enormous amount of testing to figure out how to guide an aircraft to a safe landing.

Origins

After many a British Commonwealth World War II bomber had to attempt landing through the fog, especially at night, with some failing miserably, the Royal Air Force (RAF) felt there must be a better way. So, in 1945, the RAF launched its Blind Landing Experimental Unit (BLEU).

The BLEU would be responsible for building on the work of the Telecommunications Flying Unit (TFU) in early 1945, using an American SCS 51 radio guidance system to bring a Boeing 247D in DZ203, as pictured above, down to land in pitch-black conditions. The SCS 51 used radios transmitting on different frequencies to help the aircraft, not just to triangulate its position, but to stay on a steady, safe track to the runway. Ultimately, the system was only a navigational aid that pilots could rely on until 200 feet from the runway – and then decide whether to go around or make a landing.

Love aviation history? Discover more of our stories here

Innovating An Instrument Landing System

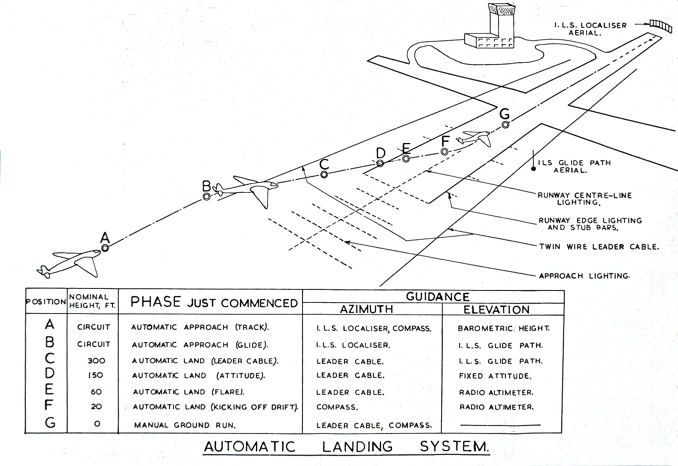

BLEU’s work would result in a new system that used radio guidance signals from the runway alongside azimuth guidance from cables strung along the runway transmitting signals. BLEU would also change the vertical guidance to an FM radio altimeter for more precise guidance down to two feet of error at low altitude – sufficiently reducing the risk for an accurate, automatic landing.

Of course, the aircraft using this system had to have an autopilot to guide the aircraft controls and an autothrottle to ensure the aircraft had the right thrust at the right time to stay on course. Autopilots and autothrottles are now standard equipment on commercial aircraft.

Read a guide about modern Instrument Landing System from an airline pilot.

Flight testing and adoption

Getting the BLEU’s work product aboard airplanes would require much flight testing. As pictured above, small airframes like the de Havilland Devon were used first, with the first demonstration on July 3, 1950. But the program was a low priority until the RAF needed jet bombers able to land in inclement weather as part of the British nuclear deterrent.

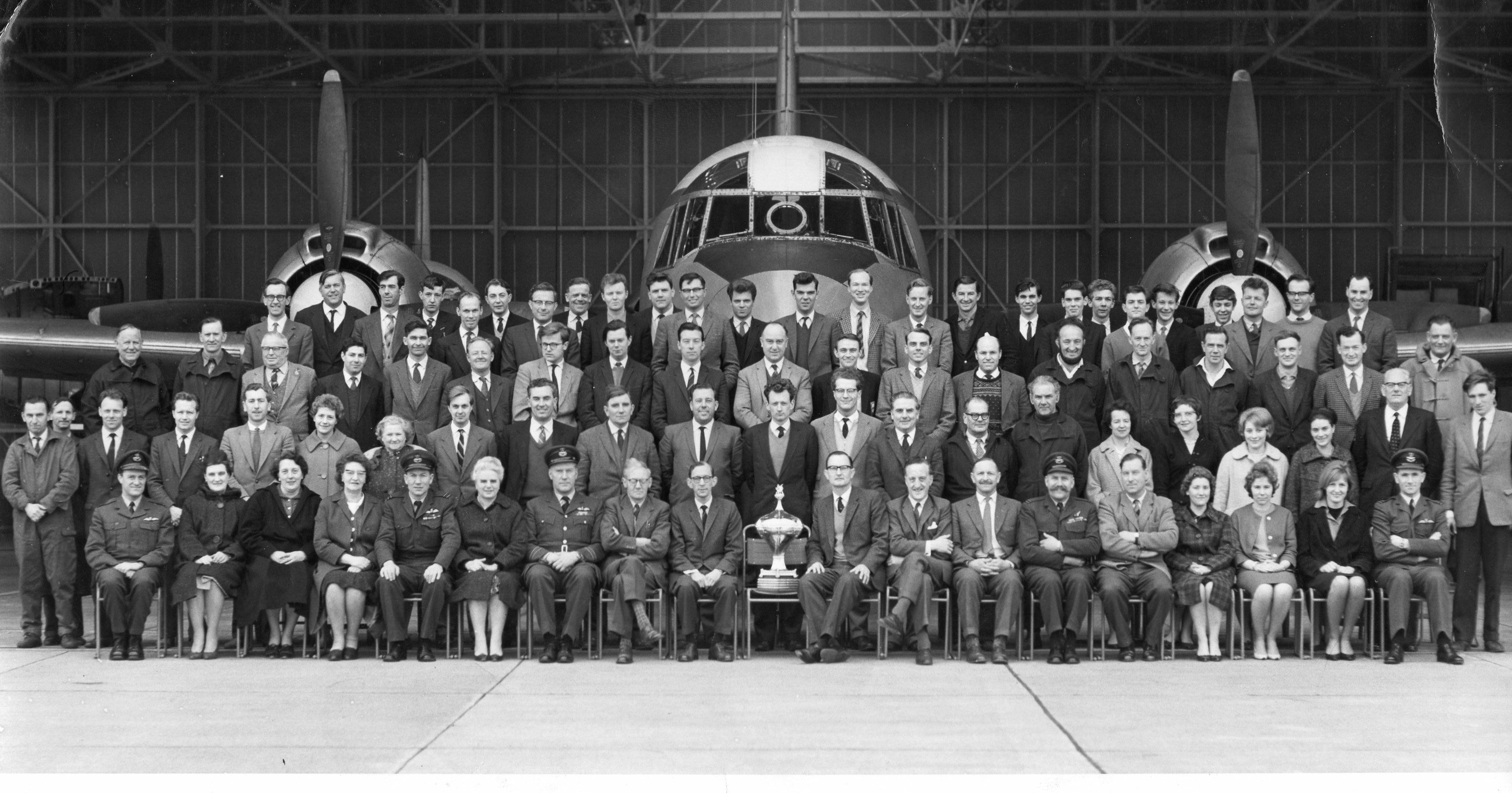

As a result, testing continued on larger airframes like the Vickers Varsity, pictured at the top of this news story, and eventually the Canberra jet bomber. Nonetheless, come 1961, despite US preferences for a human pilot in the loop, a Douglas DC-7 was used as a testing platform both at Bedford, United Kingdom, and Atlantic City, United States. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) subsequently endorsed using the BLEU’s work as a technological solution to all-weather landings.

Modern jetliners use autolanding

A review of not just YouTube but the Kindle “Boeing 737 Technical Guide” by Chris Grady shows that the current Boeing 737 Next Generation and MAX aircraft come with a Collins EDFCS-730. The Collins EDFCS-730 is an Enhanced Digital Flight Control System that controls the aircraft flight surfaces and steers the 737 to a safe landing using GPS and navigation aids like ILS.

Read a guide about autopilots from an actual airline pilot.

Unsurprisingly, Airbus also puts auto landing into their jetliners, as you can see above, using an A321 as an exemplar. Embraer, as per below, also uses autoland:

Yes, it’s normal now to wonder – did the human pilot or the autopilot land the aircraft on your next commercial flight? Nothing can replace the high safety of two trained human pilots in the cockpit.

Do you feel safer that knowing that autoland is in your commercial airliner? Let us know in the comments.

Sources: Bedford Aeronautical Heritage Group, Boeing 737 Technical Guide,