Carbon offsetting has been around for many years and has received as much negative press as positive. However, many airlines still choose to offer it as an option when booking flights. Is it worth the fee?

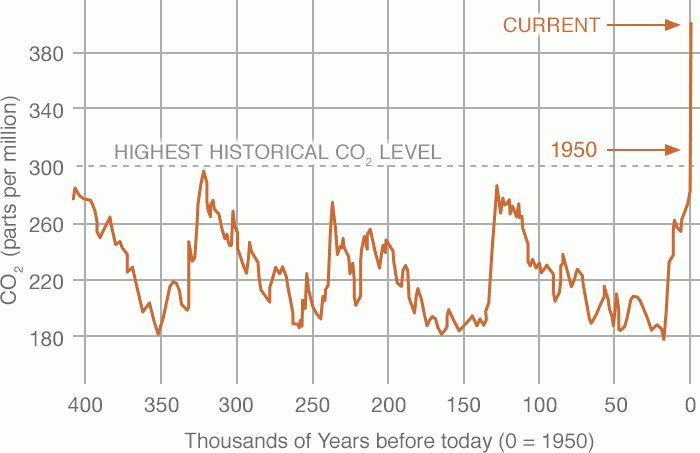

I’m not going to enter into a debate about whether climate change is real or not, but the majority of the world can agree that the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere has risen exponentially since the industrial revolution. The reason for this comes (mainly) down to our prolific use of fossil fuels.

Burning fossil fuels releases all sorts of nasties into the environment. Over the years, we’ve developed various technologies to reduce many of these, such as catalytic converters for cars and scrubbing systems for factory towers. The one we struggle with, however, is CO2. Carbon dioxide emission have increased 400% since 1950, reaching more than 400ppm in volume in the atmosphere.

Flying is one of the biggest sources of CO2 emissions, and is responsible for around 2.5% of all man made CO2 worldwide. In terms of personal carbon emissions, one long haul flight will effectively double the carbon footprint of every person on that flight for the year.

To combat the issue of flygskam, or shame of flying, airlines have long offered carbon offsetting as a means to ease our conscience. Usually this involves paying a little more for the flight, the proceeds of which will be used to do good things for the environment. But what exactly does this involve, and does it even work?

What is carbon offsetting?

Carbon offsets are voluntary schemes which see passengers paying to ‘offset’ or counterbalance the emissions produced by their flights. Flying a plane produces a number of polluting gasses which are harmful to the environment, but schemes like this focus on the most prolific (and recognizable) one, CO2.

Essentially, carbon offsetting a flight works by pegging your flight with a CO2 emission per passenger. You then pay to fund a CO2 reduction project with an amount of money that has been calculated to generate the equivalent CO2 saving to ‘offset’ your flight.

Some airlines offer this as a service themselves, giving you the option when booking a flight to pay a bit more (usually around $10 - $20) as an offset fee. There are also a number of offsetting websites set up to help you calculate the carbon cost of your journey and then make a suitable contribution to a project of your choice.

Does carbon offsetting work?

Over the years, there have been a number of scandals involving carbon offsetting schemes. Money hasn’t arrived where it should, too much disappears into ‘admin’ costs, and crucially there are only a finite number of wind farms built and trees that can be planted. Tree planting, in particular, has often been a source of contention.

Taking tree planting as an example, according to NCSU, a tree can absorb as much as 22kg of CO2 per year. Presumably this is a fully grown tree, not a sapling, but let’s go with that figure. Our return flight from LA to Chicago was pegged at approximately 454kg/CO2, so we’d need to plant 20 trees in order to completely ‘offset’ our flight.

Or, to look at it another way, that one tree we’ve helped to fund would need to grow for around 20 years before our carbon was ‘offset’, by which time we’d have probably taken a bunch more flights too. Clearly, the $10 or so we are paying for carbon offsetting won’t get us anywhere near 20 trees; in fact, it probably only covers the cost of a branch or two.

But tree planting is not the only way that carbon offsetting cash is used. There are numerous other schemes from solar farms to biogas development and even international welfare project such as efficient cooking stoves for families in developing countries.

The big argument here is whether the few dollars we pay to offset our travels are enough to really make a difference. Climate activist and Guardian journalist, George Monbiot, captured the notion back in 2006 when he said,

“How has this magic been arranged? You buy yourself a clean conscience by paying someone else to undo the harm you are causing”.

By paying to offset our carbon, are we simply commoditizing the atmosphere and very climate we live in? By paying to pollute, is it giving the green light to airlines to do less to reduce their impact on the environment?

Other solutions

A quick solution to reducing carbon from flying would be to simply stop traveling. But for most of us, that’s just not a practical (or desirable) option. However, choosing other methods of transport, where possible, can make a huge difference.

As an example, traveling from London to Paris on a plane comes with a per passenger equivalent of 244kg/CO2. Taking the same journey on the Eurostar is actually faster and leads to only 22kg/CO2 - a 91% saving. Of course, not all journeys are quite this easy to substitute; for example, to get to Tangier overland would reduce CO2 by 85% but would take two days compared to five hours on a plane. (TOTH to Seat61 for these figures).

Choosing our airline for having newer, more efficient aircraft can help too. There’s been a massive reduction in fuel consumption over the past few decades, so clearly flying on a highly efficient A320neo is going to work out better than taking an aging 767 for our trip. Flying with fewer connections is a great strategy too, as aircraft use the most fuel on takeoff.

The good news is that, in many parts of the world, the offsetting question is being taken out of our hands. In North America, for example, by 2021, airlines that fly internationally will need to offset their CO2 emissions under a UN agreement. The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation was agreed in Montreal last year, and will see airlines themselves making offset contributions based on the carbon they produce.

In a nutshell, is carbon offsetting the answer to all our problems? Probably not. But it does do some good. Projects funded through these contributions are driving innovation and making big changes in some parts of the world. Airlines, whether driven by cost or conscience, are also making great strides in becoming more efficient. And, of course, the manufacturers are constantly improving the planes we fly on, so that they do less harm with each flight.

Carbon offsetting is always going to be a contentious issue, and up for debate regarding its effectiveness. However, in my opinion, if I fly and I can afford to offset, why wouldn’t I?