Landing in crosswinds is always a challenge for pilots, but it is something that becomes almost second nature once the experience is gained. It requires well-learned techniques and muscle memory to perform a good crosswind landing.

Aerodynamics of a crosswind

So, why do aircraft point sideways in crosswind conditions? Interestingly, it is not the pilots that point the aircraft sideways, the aircraft does it automatically. This happens because they are designed with a certain amount of directional stability.

When the airflow hits an aircraft from the side, it experiences something called a sideslip. This is an undesirable aircraft state, which increases drag. If the aircraft has directional stability, it immediately tries to eliminate the sideslip and align itself with the airflow.

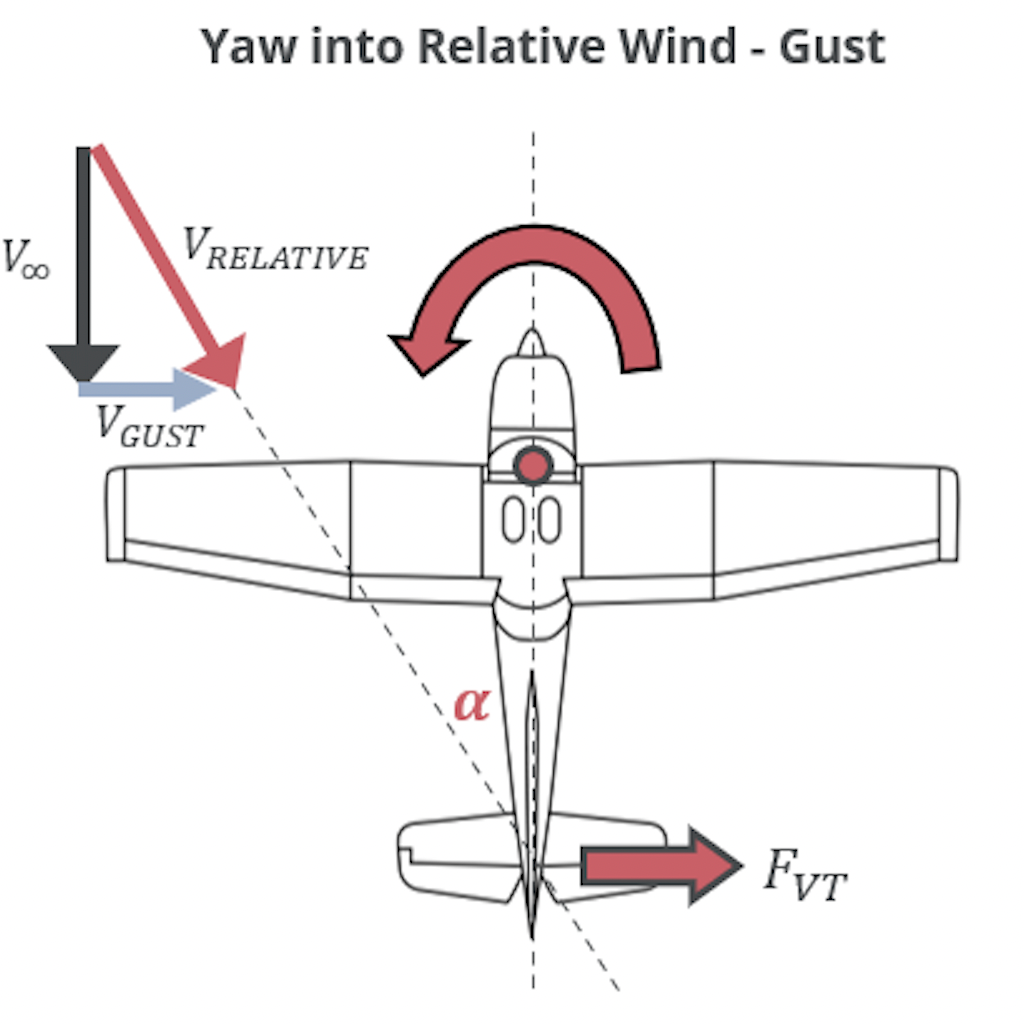

The greatest contributing factor to directional stability is the vertical stabilizer or the fin of the aircraft. For instance, if the wind is coming from the left, the air hits the stabilizer from the left, generating a lifting force that acts through the aircraft's center of gravity to point it to the airflow. In this case, it will point the aircraft's nose to the left.

When a gust attacks the aircraft from the left, a lifting force is generated on the rudder, which aligns the aircraft with the wind. Photo: aerotoolbox

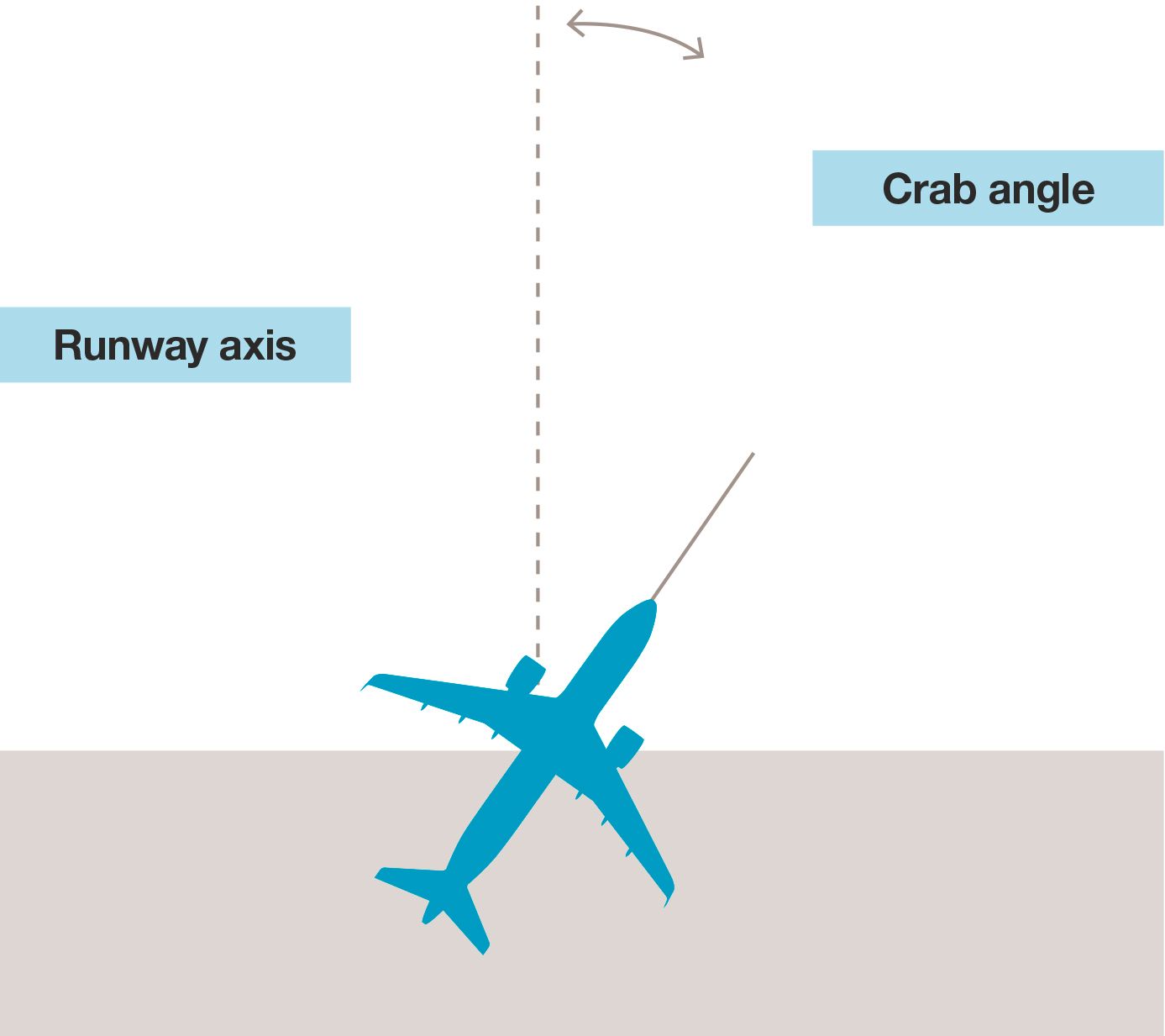

This sideways pointing of aircraft is called crabbing. Why is it called crabbing? It is because, in a crosswind, the aircraft's nose is pointed in one direction with its track or flight path going in an entirely different direction. This mimics a crab walking on a beach, with it facing one direction while moving in a different direction.

The piloting technique for crosswinds varies from aircraft to aircraft. There are two main methods. One is the crab method, and the other is the wing-down method.

The wing-down method

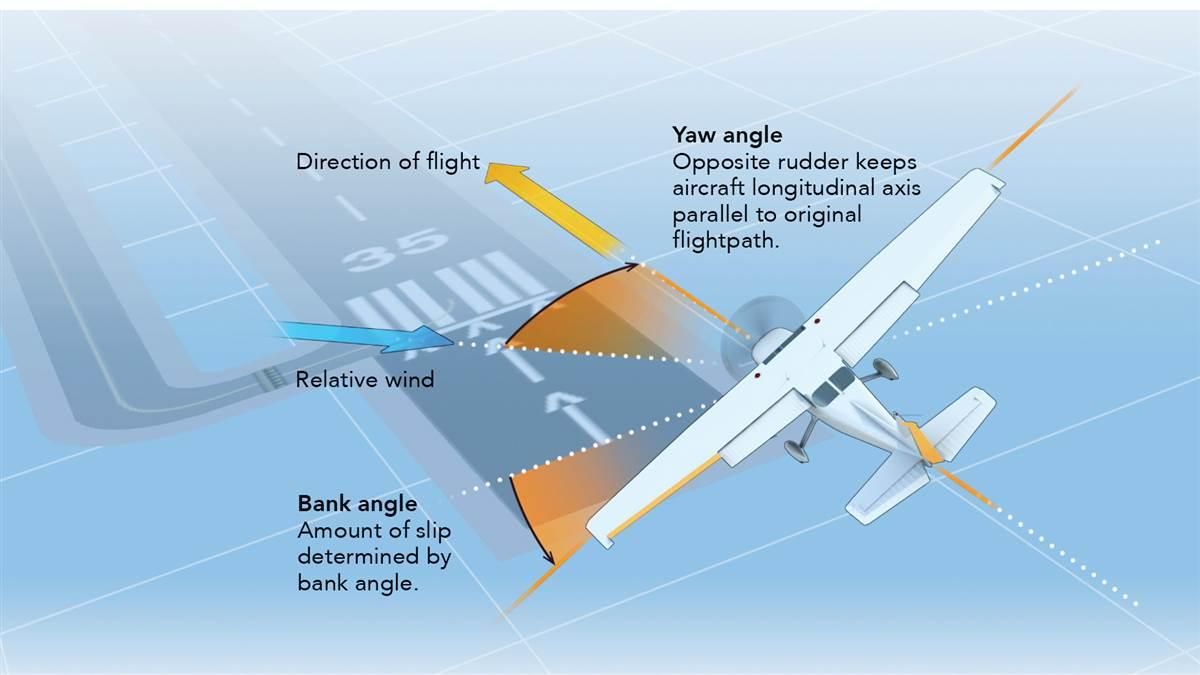

The wing-down method is a crosswind approach and landing technique where the pilot knowingly puts the aircraft in a sideslip. To do so, the rudder is applied to align the aircraft to the runway center line which straightens the aircraft. This action causes the lift to increase on the upwind wing and a rolling action is generated which can make the aircraft drift. Thus, to prevent the drift, the pilot uses the roll controls to lower the upwind wing.

This is called cross controlling, where the rudder is applied to the opposite direction of the yoke/stick/sidestick. The pilot must vary the control inputs per the intensity of the wind to keep the aircraft right on the center line with no drift whatsoever. The wing-down method is usually utilized down to the touchdown. In this state, most of the time, the upwind landing gear hits first on the ground.

This method is very easy in terms of piloting, as there is no change of technique required for the landing, and it gives a better feel of the changing wind for the pilot which gives better controllability.

The crab method

In the crab method, the pilot maintains the aircraft in a crab. The pilot simply keeps the aircraft's flight path right on the runway centerline with its nose pointed into the wind. For this technique, little to no rudder input is required. The complexity of this technique is that at the very end the pilot must change over to the wing-down method. We call this kicking out the crab.

The reason we cancel the crab is because landing in a crab can put side loads on the landing gear which can damage it. The crab is more of an approach technique rather than a landing technique as, for most aircraft, touching down with a crab is not an option.

There are also certain advantages the crab method has over the wing-down method. They are:

- There is less drag on the airframe which reduces fuel burn

- Less engine thrust changes are required during the approach

- Not much change of control surface deflection is required during the approach, until the very last seconds before the touch-down when the wind becomes more predictable

- If carrying passengers, the crab method is more comfortable for them.

Mixing both methods

For smaller aircraft and some turboprops, the only method to land in a crosswind is a zero-crab wing down the landing. But when it comes to larger aircraft such as most jet aircraft, landing with some crab is acceptable. This is because these aircraft are designed with low wings and underslung engines and banking the wing close to the ground can lead to a wing tip or an engine nacelle strike.

In turboprops with straight wings, a crosswind landing is very similar to that of small general aviation aircraft. You can use the wing down method all the way to the landing or use the crab method, kicking it out in the end.

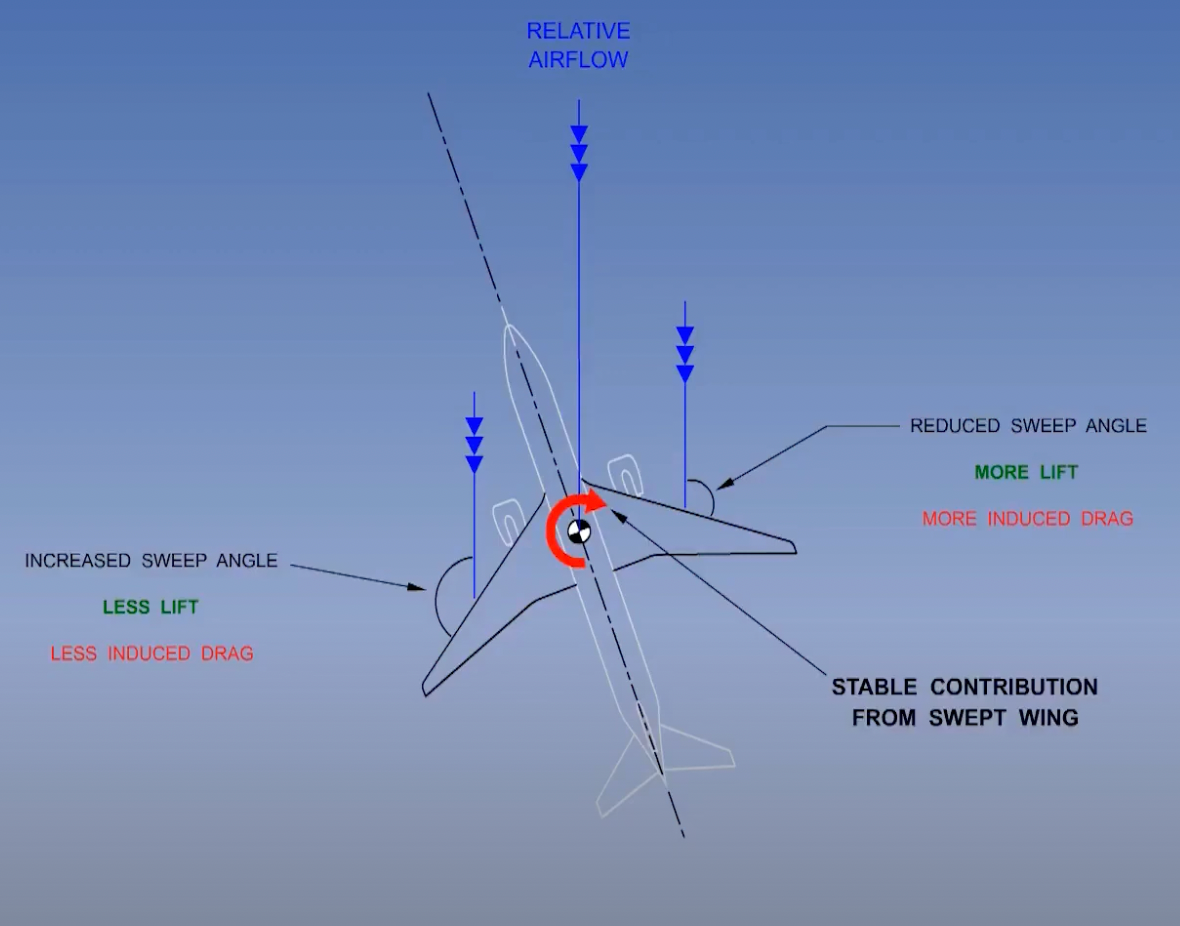

In a swept-winged jet, however, things are a bit different. The wing-down technique can be used with caution, but it is not recommended. One of the reasons is because of the way the swept wings react to a sideslip which requires more rudder input to align the aircraft with the runway, as swept wings give a bit of additional directional stability and try to prevent the aircraft from going into a sideslip.

In a slip, the upwind wing experiences less of a sweep angle than the downwind wing which causes it to generate more lift. This results in more induced drag which tries to align the aircraft into the wind. This increase in lift also causes the aircraft to roll, which requires more counter roll input from the pilot to keep the aircraft from drifting.

The wing-down method as discussed previously also requires more thrust to maintain the approach speed due to the additional drag. Jet engines naturally have slower spooling times and utilizing this method in a jet aircraft makes thrust control more difficult. And it is not only the drag from the sideslip. As the roll controls and rudder controls are deflected, there is also a considerable amount of control surface drag which adds to the drag profile of the aircraft making the flight more and more inefficient.

So, for a jet aircraft, the preferred technique is the crab. The crab is maintained until the flare for the landing. In the flare, the crab can be kicked out, and roll control added as necessary to prevent the drift. Here, care should be taken not to kick out the crab too quickly, particularly when very close to the ground as the sudden increase in drag can cause the aircraft to drop like a brick. The crab should be zeroed out at about 20-30 ft (flare height) off the runway for most mid-sized to large jetliners.

In strong crosswinds, partial de-crab is highly recommended, so the aircraft lands with the nose pointed partly sideways. This prevents high bank angles which reduces the risk of the wing tip touching the runway. In normal circumstances, as soon as the main wheels of the aircraft hit the ground, the friction causes the nose to point to the runway centerline, so the directional control of the aircraft is hardly affected by landing with a slight crab angle.

On wet runways, due to the reduced friction, this does not happen that neatly. That is why for wet runways the maximum crosswind component is reduced by the aircraft manufacturer. One might now wonder why jet aircraft are allowed to land in a crab. This is mainly down to the landing gear design. These aircraft have a special side strut in the gear which takes most of the side loads unlike those super straight landing gear found in general aviation aircraft and turboprops.

.jpeg)