Elizabeth “Elsie” MacGill made an indelible mark on the aviation industry in an era when there were limited opportunities for women in engineering. Guided by her passions and intellectual interests, she achieved numerous “firsts” in her educational and professional careers. Elsie MacGill was the first woman to receive an electrical engineering degree and is recognized as the first woman aircraft designer in the world.

Let’s explore the life of Elsie MacGill and her remarkable contributions to the aviation field.

Family influence and educational achievements

Elsie MacGill was born on March 27, 1905, in Vancouver, British Columbia. Even from a young age, she learned that women could achieve anything they desired. Her grandmother had fought for women’s right to vote, and her mother was the first woman in the British Empire to earn a bachelor’s degree in music.

She enrolled in the University of British Columbia to study applied science, then switched to the University of Toronto’s School of Practical Science in 1923. MacGill was the first woman ever admitted to the institution’s engineering program. After graduating in 1927, she began her professional career as a mechanical engineer for an automobile company in Pontiac, Michigan, in the United States. Her interest in aeronautics was piqued when the company started manufacturing aircraft.

MacGill enrolled at the University of Michigan to study aeronautics and graduated with her master’s degree in 1929, making her the first woman aeronautical engineer. Unfortunately, she was diagnosed with polio that same year. She returned to Canada to recover and was temporarily confined to a wheelchair.

However, contracting polio did not hamper her zeal for her newfound professional field. She made productive use of this time by creating aircraft designs and writing articles for aviation publications.

“Queen of the Hurricanes”

Elsie MacGill survived polio and even managed to resume walking with the help of canes. In 1934, she was offered a job as an assistant aeronautical engineer at Fairchild Aircraft in Quebec. During her four-year tenure with the company, she drafted aircraft designs and participated in test flights to evaluate the aircraft’s performance.

In 1938, she took on the role that would bring her the most notoriety—chief aeronautical engineer for the Canadian Car & Foundry company in Ontario, Canada. One of her major projects was a complete redesign of the Maple Leaf Trainer, which McGill designed to British requirements for strength. The aircraft did not ultimately go into production, but McGill was heralded for having overseen its development from design through the testing process.

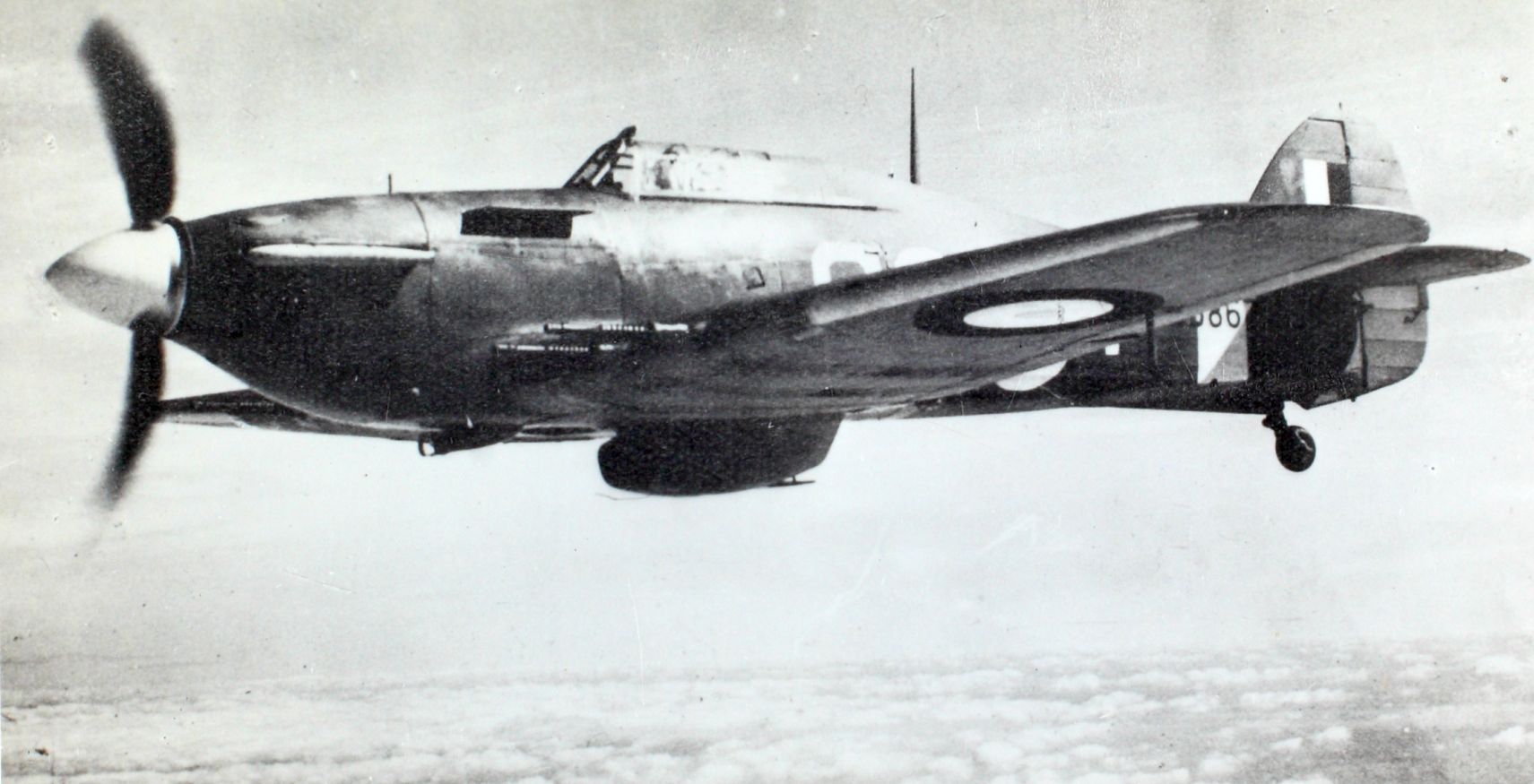

Building upon her success with the Maple Leaf II, Elsie McGill was then tasked with overseeing the plant’s mass production of the Hawker Hurricane fighter plane that was flown by Canadian and Allied forces during the Second World War. She was 35 years old at the time. Taking on this responsibility garnered much attention for McGill. In 1942, the American True Comics published a series about her entitled “Queen of the Hurricanes.” She oversaw the production of 1,451 aircraft during the war.

Get the latest aviation news straight to your inbox: Sign up for our newsletters today.

Later career

The Canadian Car & Foundry company’s contract for the Hawker Hurricane concluded in 1943. Elsie McGill and the plant manager, E.J. Soulsby, left the company soon after. They married and settled in Toronto, Ontario. McGill then started her own engineering consulting firm, primarily working with clients in the civilian aviation field.

She contributed her expertise to professional organizations and was civically engaged, following in the footsteps of her grandmother. McGill was the first female member of the Engineering Institute of Canada and maintained close ties with her colleagues throughout her career. She served as the Canadian representative in the International Civil Aviation Organization and was the first woman entrusted to provide technical expertise on aircraft airworthiness. In the late 1960s, she was a member of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada.

The “Queen of the Hurricanes” died in 1980, but her legendary achievements have made a long-lasting impact on the aviation industry.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)