Despite growing up a few miles apart in Manchester, north-west England, John Alcock, and Arthur Brown did not meet each other until after the First World War. Both mad keen on flying and inspired by pilots like Tommy Sopwith, Freddie Raynham, and Harry Hawker, both men joined the military with Alcock joining the Royal Naval Air Service and Brown the Royal Flying Corps as an observer. They both also had the misfortune of crashing behind enemy lines and spent considerable time in enemy prisons.

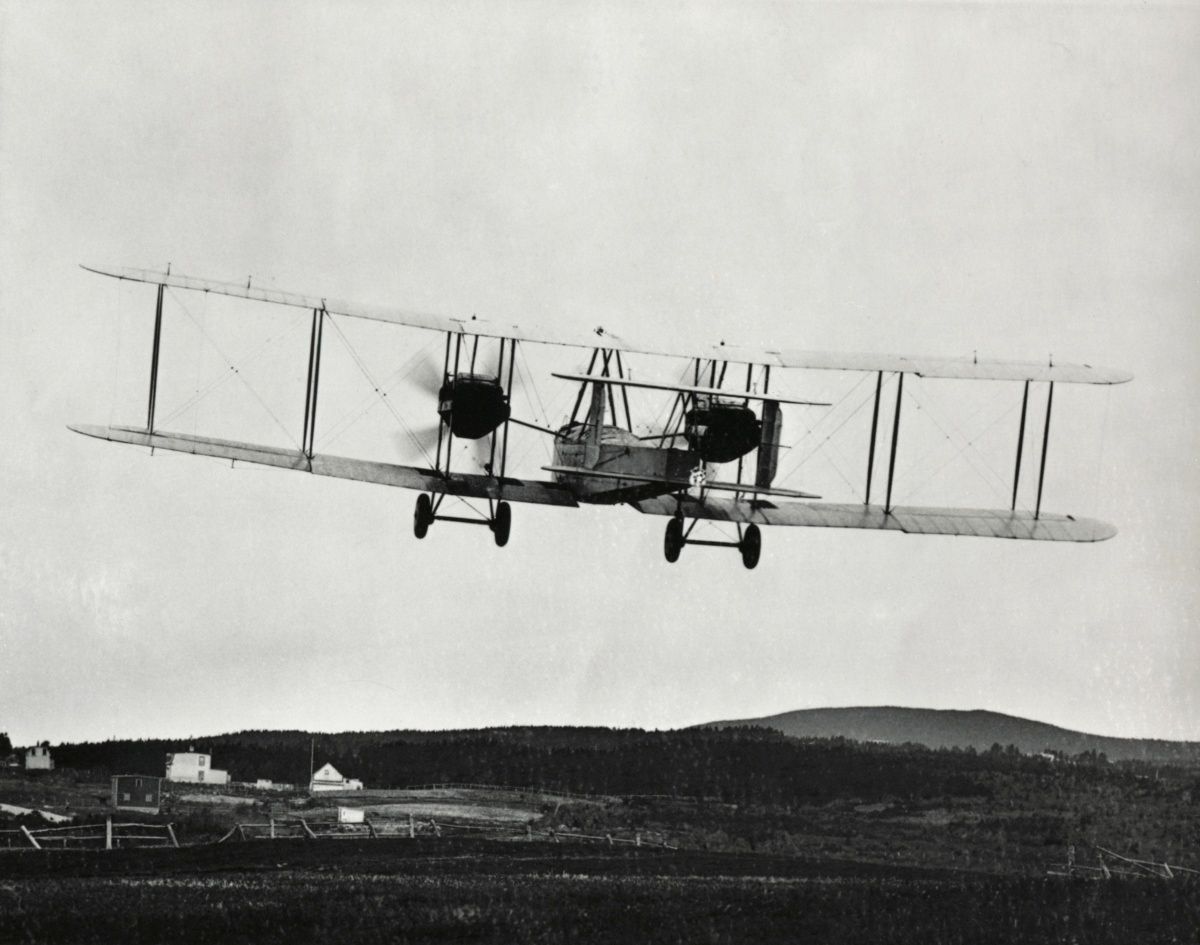

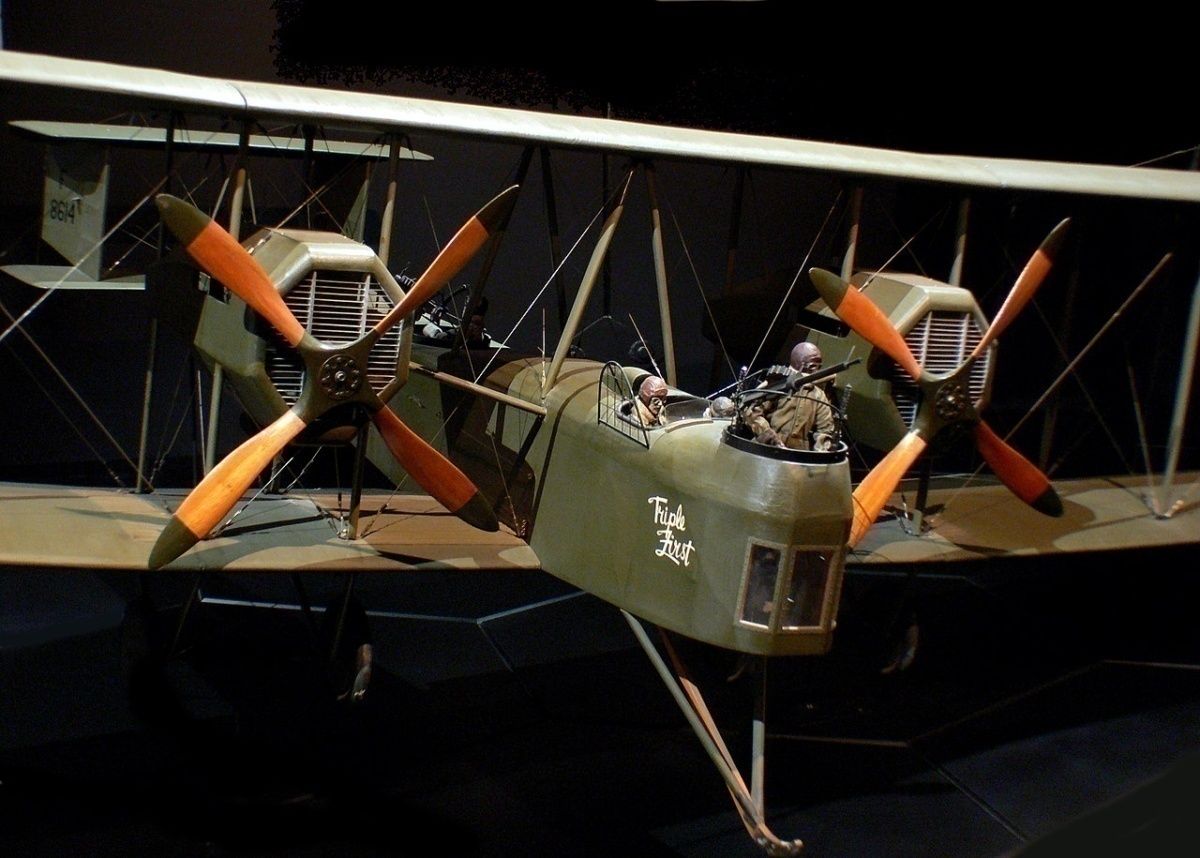

A Vickers Vimy was chosen for the Atlantic crossing

Before war broke out in 1914, British newspaper The Daily Mail came up with the idea of offering £10,000 for the first non-stop flight from anywhere in North America to either Britain or Ireland. At the time, most aviators thought that the distance was too far, Atlantic storms too overpowering, and that no one truly knew how to fly long distances over water.

After the war, both men were interested in competing for the Daily Mail prize, a topic of conversation that came up when they met at Brooklands in 1919. After striking up a friendship, the two decided that they would attempt to fly from Newfoundland in Canada to Ireland using a twin-engine Vickers Vimy bomber.

By the time the pair arrived in St.Johns, they were the rank outsiders with three other teams competing for the prize. One of the groups included Harry Hawker, an aviator that Alcock had idolized as a boy.

Previous challenges

While stuck in Newfoundland waiting for their plane to arrive from London, Hawker and his navigator Kenneth Mackenzie Grieve made their attempt in a Sopwith Atlantic biplane. Unbeknownst to Alcock and Brown, the engine in Hawker's plane started to overheat. This forced them to divert to shipping lanes in the hope of being able to ditch near a passing ship.

Fortunately for the pair, they came upon a passing freighter named Mary, who managed to pluck them from the sea. With the Danish cargo ship not having a functioning radio, news of the failed attempt did not reach Alcock and Brown until the Mary docked at Butt on the Isle of Lewis six days later.

The Vimy finally arrived on May 26 with all of its parts packed in crates that Vicker's mechanics would have to put back together. Once the plane was assembled, a makeshift runway needed to be built from where they could take off. When the pair were finally ready to depart, strong gusting winds were a concern as were the rumors that another team led by Admiral Mark Kerr was also prepared to leave for Europe.

If they were to depart sooner than Alcock and Brown, the chance of the prize and the record would be gone. Spurned on by this, the pair put on their flying suits and threw caution to the wind.

Sea fog made it tough to navigate

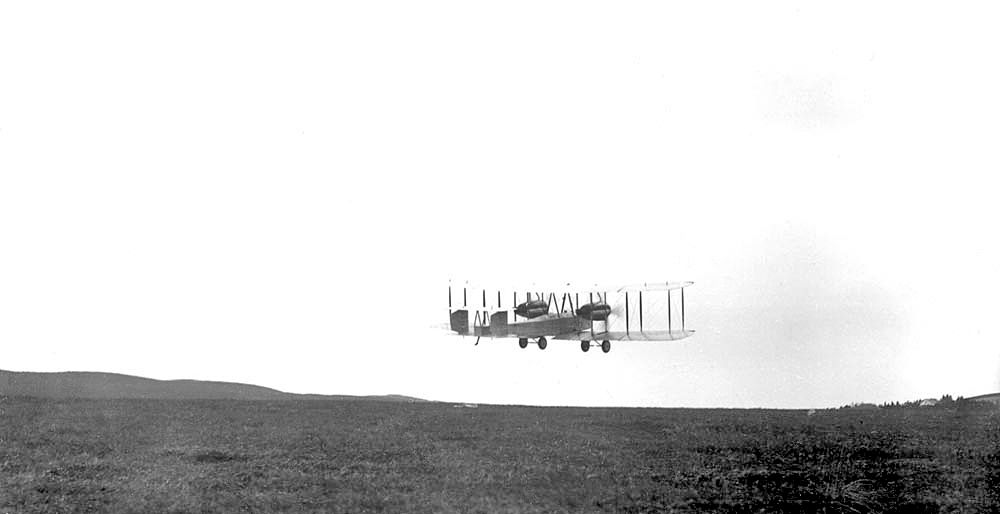

Weighed down by all the extra fuel, the aircraft barely made it into the air before running out of runway. For the beginning of the flight, the men enjoyed pleasant conditions with bright sunshine sparkling off the icebergs below. However, this was about to change as they suddenly flew into a bank of thick sea fog. Brown was then unable to navigate by the sun. Therefore, he was forced to calculate their position by dead reckoning. This was a precise navigation method that could see them flying miles off course.

Brown attempted to send a message using their wireless transmitter only to see a vital part break and fall off. To make matters worse, a piece of the plane's exhaust had fallen off. This incident created such noise that the two could only communicate with pen and paper.

The adventure continued

After several hours of flying blind, Alcock decided to gain altitude in an attempt to allow Brown to get a reading on their position. Despite still being in a thinner level of cloud, Brown was able to see the pole star and Vega. Using these two points as a guide, Brown was able to calculate where they were.

The position was around 850 miles from the halfway point of the journey from what he had discerned. As dawn broke, the wind picked up, causing the Vimy to shimmer and then stall. Now spiraling down through cloud and unable to see the horizon, Alcock managed to regain control just feet above the sea. Once he had restored his balance and centralized the steering, Alcock opened the throttle bringing life back to the massive Rolls-Royce engines.

Alcock thought he was landing in a meadow

As the plane gained altitude, the pair encountered sleet, snow, and ice as Alcock struggled to keep them level. Suddenly without warning, Brown felt Alcock grab his shoulder and then point to specks of green in the distance that could only be small islands off the coast of Ireland. Knowing his job was now done, Brown put away his charts and let out a massive sigh of relief.

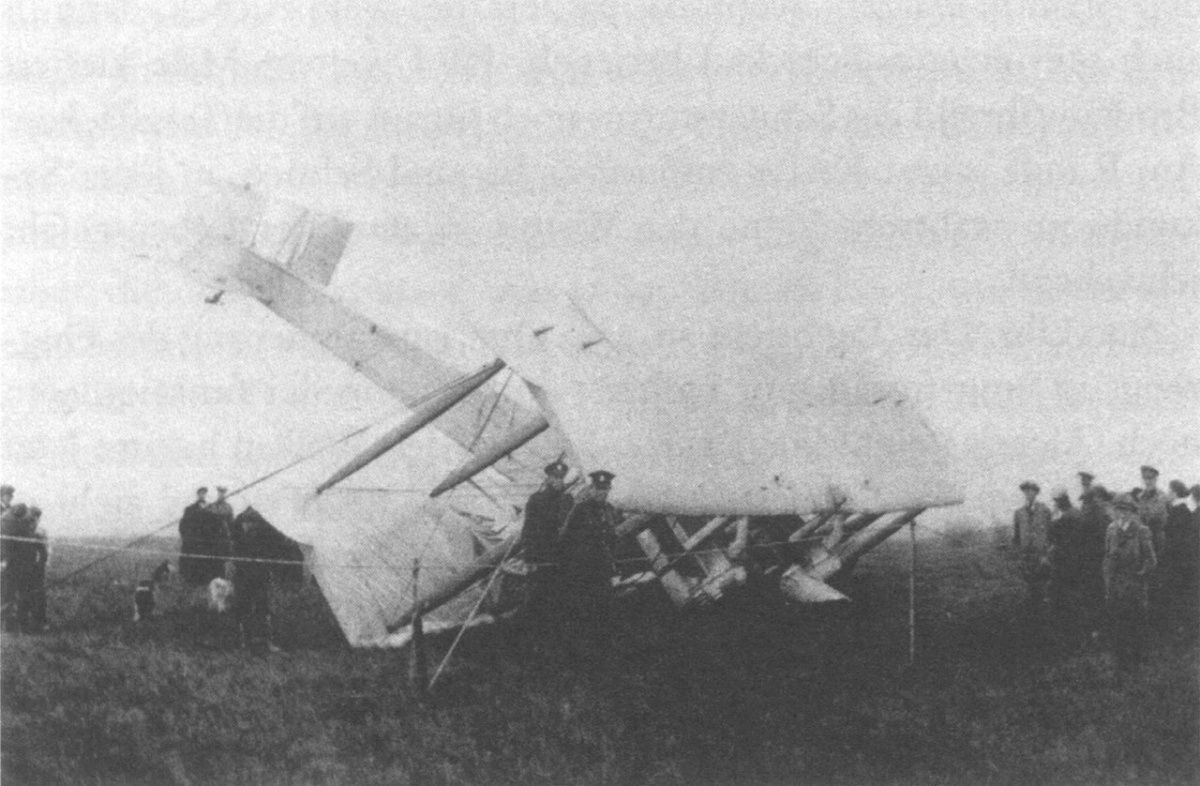

As the pair crossed the Irish coast at around eight-thirty in the morning, Alcock immediately looked for a place where he could land. After seeing what he thought was a flat meadow, Alcock brought the Vimy down. He performed what he thought was a perfect landing before the plane pivoted nose-first into a peat bog.

As the two pilots scrambled to get out of the aircraft, locals, some of whom were still dressed in pajamas, came running towards them.

The BBC quotes the following conversation as taking place,

"Is anybody hurt?" somebody asked the pair. "No." they answered despite blood running from Brown's nose.

"Where are you from?" said another. "America," Alcock replied. The crowd laughed, refusing to believe that they could have arrived from so far away.

When the two airmen asked for news about the rival team led by Admiral Kerr, they just drew blank faces. They needn't worry, though, as they were the first team to arrive in Ireland 15 hours and 57 minutes after departing Newfoundland.

King George V knighted both men at Windsor Castle

Following the accomplishment, both men were treated as heroes. In addition to their share of the £10,000, Alcock received £2,100 from the State Express Cigarette Company and £1,000 from Laurence R Philipps for being the first British pilot to cross the Atlantic. A few days after being back in England, both men were knighted by King George V. This event took place at a reception held in Windsor Castle.

Sadly for John Alcock, his fame was short-lived. Unfortunately, he died in a crash near Rouen while flying a new Vickers Viking to the Paris Air Show.

As for Brown, he continued to work in the aviation industry before joining the RAF during the Second World War. However,, his health deteriorated following his only son's death after being shot down over the Netherlands. Brown later died in his sleep on October 4, 1948, after accidentally overdosing on sleeping pills aged 62.

What do you think of Alcock and Brown's historic journey? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments.