So-called autoland systems are a part of aircraft autopilots. All large modern jets are equipped with such systems, which can automatically land the aircraft, albeit under careful supervision from the pilots themselves. This can be used for any landing where the airport is equipped to offer it, and weather conditions allow it.

Developed to allow landings in bad weather

Research into autoland systems began in the years after the Second World War. This was a time when commercial aviation was expanding rapidly, and airlines began to face challenges with bad weather and low visibility at some airports. British European Airways (BEA), in particular, was very keen to find a solution, as its UK operations were often affected for several days by poor visibility.

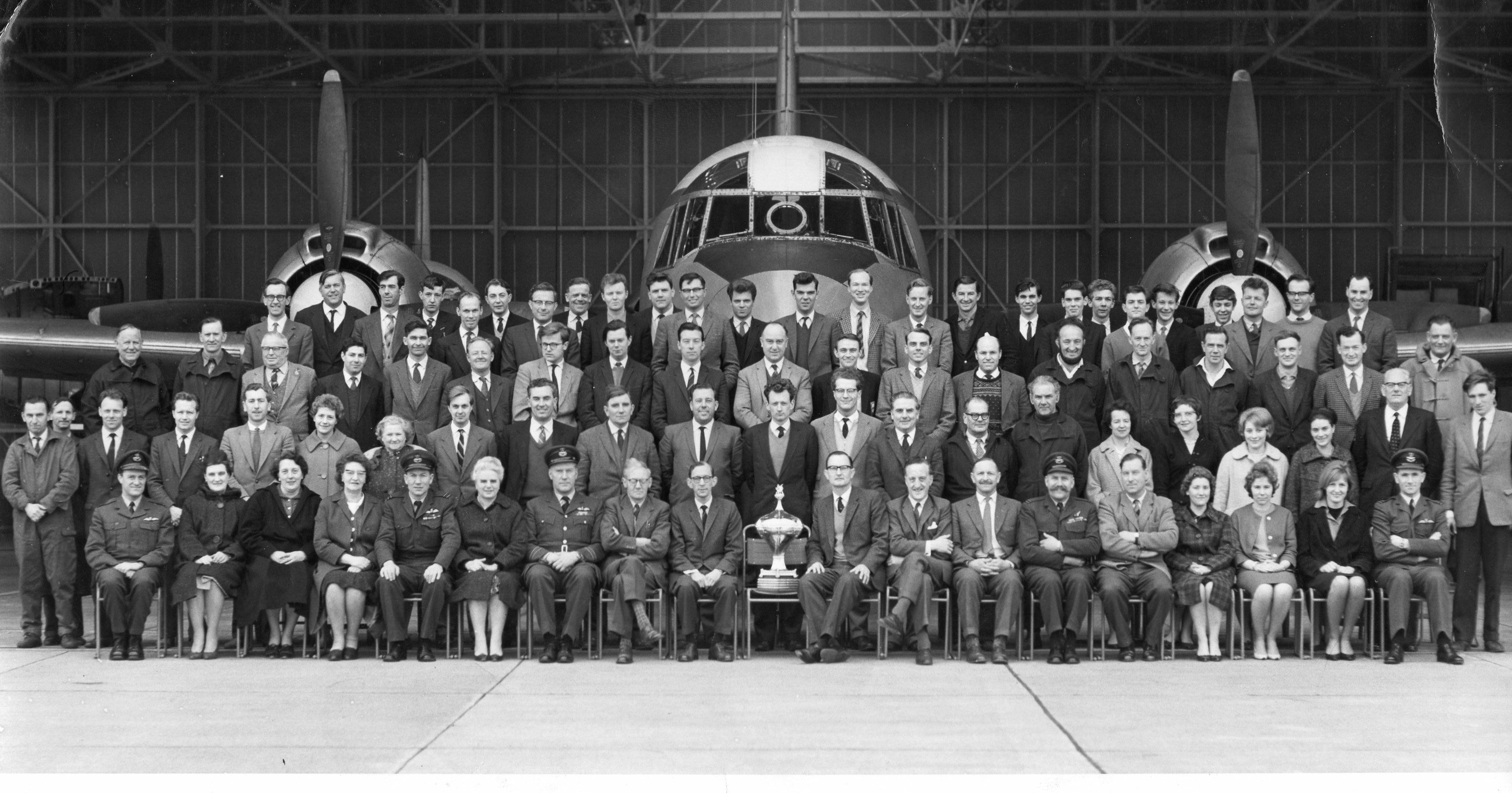

Unsurprisingly, given its fog and poor weather, this work was largely led by the UK. A key group performing research in this field was the Blind Landing Experimental Unit (BLEU), which was launched by the country's Royal Air Force (RAF). The BLEU's work saw it use an American SCS 51 radio guidance system onboard a Boeing 247D, and it ultimately paved the way for future autoland systems.

Love aviation history? Discover more of our stories here!

Autoland systems built on the existence of several other useful cockpit aids, including ILS (which had been in limited use since before the Second World War), and the aircraft autopilot system. Such systems were first used in military aircraft, with BEA's Hawker Siddeley Trident fleet starting to offer autoland in the 1960s.

The technology soon appeared on many other aircraft types. The Sud Aviation Caravelle was another early adopter. Today, they are standard on all large commercial jets and an option on most business jets, but how do they work?

Autoland operations

The operation of autoland systems has developed and improved since these earliest systems in the 1960s, but the principles are the same. Autoland on commercial Boeing and Airbus jets works through the normal autopilot systems. Pilots input relevant data using the Flight Management System, then configure the autopilot to handle the landing, making use of several systems and onboard equipment.

Want answers to more key questions in aviation? Check out the rest of our guides here!

For example, the Instrument Landing System (ILS) is needed for the localizer and glide slope signals, and a radio altimeter for height determination, as the aircraft will establish and maintain the correct approach using the ILS. Auto-thrust is vital too, to maintain the correct approach speed. At the appropriate altitude (determined by the altimeter), autoland will initiate the flare, by reducing thrust and pitching up.

At all times, pilots must closely supervise the autoland process. There are well-documented and practiced methods for pilot takeover, with a missed approach standard in the event of any system problems. All in all, it is a safe practice.

When it comes to ground operation, there are certain procedural differences between various aircraft types. Autoland will slow the aircraft after landing. It may or may not be able to steer the aircraft on the ground, depending on whether it can control the nose wheel. If not, pilots must take over immediately after landing.

Multiple autopilot systems

Autoland usually makes use of several (typically three) independent autopilot systems. Such redundancy is needed for safe operation. If one set of inputs differs, it can be ignored, and a safe landing can continue with the other autopilots. Such a situation is known as "fail passive," and the landing can continue regardless.

When is autoland used?

Autoland systems are generally made use of in low visibility or fog conditions, but not with strong crosswinds (there are crosswind limitations set for each aircraft type). Furthermore, the arrival airport in question must also be capable of handling autoland operations. Specifically, it needs to have a CAT III ILS-equipped runway.

Passengers may think that, as they are able to, aircraft will self-land most of the time. However, as it happens, this is not generally the case. Pilot comments on the blog Flight Deck Friend indicate that autoland is used only around 1% of the time. A key reason behind this is that pilots often find manual landings easier.

Recent concerns

The recent rollout of C-band 5G cellular networks has proved to be something of a cause for concern when it comes to the use of autoland systems. Indeed, as Simple Flying reported last year, fears of interference with radio altimeter equipment meant that autoland systems would have to be disabled at 100 US airports.

This has been a quick overview of autoland's development and operations. There is much more to discuss about flight operations, ILS, and aircraft autopilots. Feel free to do so in the comments!

Source: Flight Deck Friend