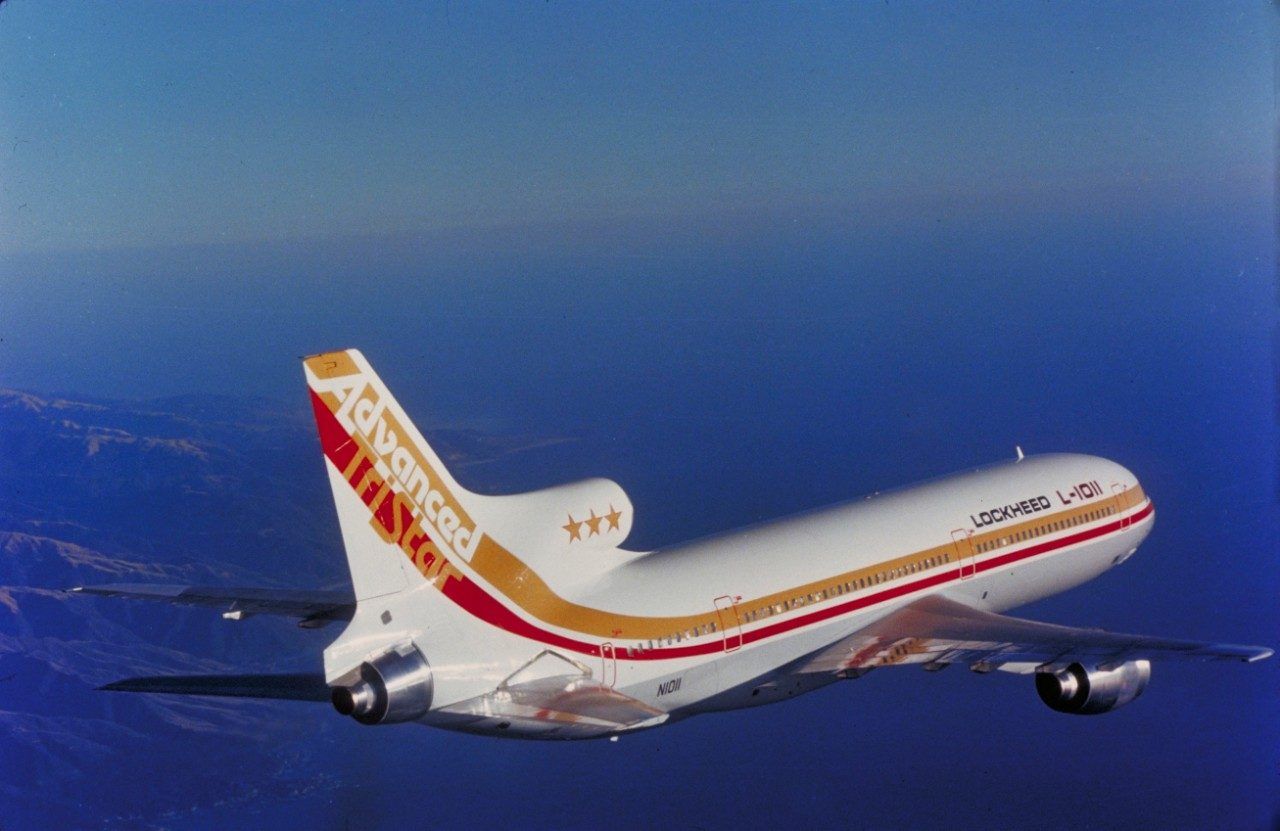

Exactly 52 years ago today, on November 16, 1970, the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar made its maiden flight. Test pilot Henry Baird Dees, copilot Ralph C. Cokely, and test engineers Glenn E. Fisher and Rod Bray made up the crew. The aircraft took off from Lockheed's Palmdale, California plant in the California high desert and flew the plane for two and a half hours. During the maiden flight, the aircraft reached an altitude of 20,000 feet and a speed of 288 miles per hour.

Looking for a plane that could carry 250 passengers, American Airlines approached Lockheed and rival Douglas to see if they could build an aircraft suitable for transcontinental flights. The last time Lockheed had built a civilian airliner was in 1961 when it manufactured the Lockheed L-188 Electra. Back then, the turboprop was the engine of choice, but since then, aviation had entered the jet age.

Lockheed was keen to get back into civilian aviation

After having experienced difficulties with some of its military contracts, Lockheed was eager to get back into civil aviation. The response to American Airlines' request was a small widebody airliner called the L-1011 TriStar. Meanwhile, Rival Douglas came up with a similar three-engine design called the Douglas DC-10.

Despite both planes being powered by three engines, the designs differed significantly. Douglas had recently been taken over by McDonnell, who was very cost-conscious, using technology from the existing DC-8 for the DC-10. Lockheed set out on a different path using the latest aerospace innovations for its plane. Because it was using more advanced technology than the DC-10, the price of the TriStar was higher.

Lockheed decided to go with Rolls-Royce engines

Initially conceived as a twin-engine jumbo jet, three engines were selected to power the plane and give it extra thrust on takeoff. Another factor was that in the era before ETOPS, twin-engine planes could fly only 30 minutes from an airport, making ocean crossings impossible. Looking at the two planes side by side, the main difference was the DC-10's central tail engine, while the TriStar's was fed through an S-duct similar to the Boeing 727.

Another difference between the two jets was Lockheed's decision to use the Rolls-Royce RB211 engine. At the time, the Rolls-Royce engine was more efficient and had a better power-to-weight ratio than the General Electric CF6 that Douglas had selected for the DC-10.

Now shunned by American, the TriStar had to rely on TWA and Eastern Airlines for orders.

Rolls-Royce entered receivership

Because it was primarily built from existing technology, the DC-10 launched a year ahead of the TriStar. Lockheed was hindered by financial problems at Rolls-Royce, which saw the British engine maker enter receivership in 1971. This halted the supply of engines forcing Lockheed to look for an American engine to power the plane. Unfortunately, the TriStars S-duct design was too small for any existing engine other than the RB-211.

The British government stepped in and gave Rolls-Royce a subsidy to restart operations on condition that the United States government guaranteed loans Lockheed needed to complete the L-1011 project. In 1972, after years of unforeseen setbacks, Lockheed delivered the most technologically advanced commercial jet of its era to launch customer Eastern Airlines.

Eastern Airlines began commercial service with the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar on April 30, 1972, with a flight between Miami and New York. While we may take the technology for granted now, the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar was the first commercial airliner that could fly itself from takeoff to landing.

In total, during its production run between 1968 and 1984, 250 Lockheed built 250 L-1011 TriStars.

Get the latest aviation news straight to your inbox: Sign up for our newsletters today.