As airlines worldwide look to lower their carbon emissions, other than electric-powered planes, the only natural alternative is hydrogen. To make this happen, several companies, including European planemaker Airbus, are hard at work trying to develop aircraft that will use hydrogen to power their engines.

Using hydrogen to power aircraft engines is not a new concept. It has already been used for a Martin B-57 Canberra twin-engined tactical bomber and re aircraft. Back in the 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union were already locked in a Cold War. The Americans regularly used Lockheed U-2 spy planes for missions but wanted an aircraft that could fly at altitudes beyond the range of Soviet ground-to-air missiles. Using standard JP-4 jet fuel, the U-2 had an absolute ceiling of around 60,000 ft to 65,600 ft.

Project Bee

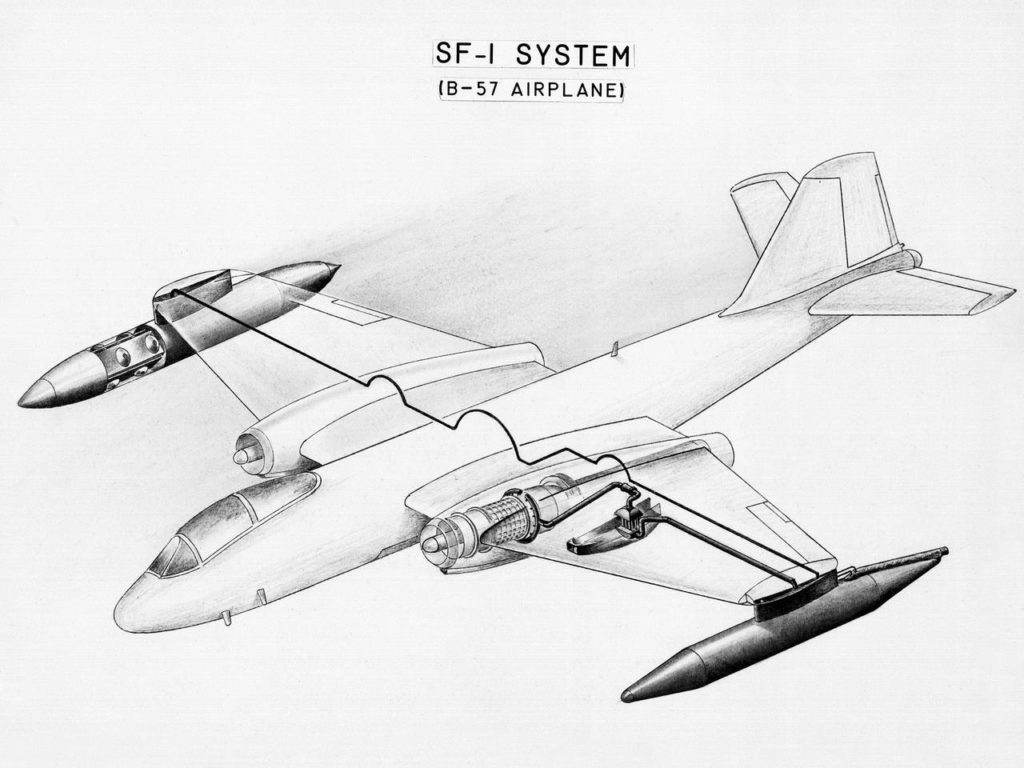

Given the code name "Project B," the task of powering an aircraft with hydrogen was given to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). At its Lewis, Flight Propulsion Laboratory engineers found that the absolute ceiling for a plane could be as high as 90,000 ft when using hydrogen as fuel. Because the wind tunnel tests were performed using a Wright J65 axial-flow turbojet engine, the Martin B-57B Canberra was chosen to be the test aircraft. The plan was to equip the plane with an independent hydrogen fuel system separated from its regular jet fuel system. The engines also needed to be modified to operate using either jet fuel or hydrogen.

The plan was for the aircraft to take off using standard jet fuel and that once it got to an altitude of 50,000 ft, switch one of the engines to run on hydrogen. When the hydrogen experiment was over, the plane switched back to jet fuel for landing. During the aircraft's conversion, it was fitted with two specially built wingtip tanks, one containing hydrogen and the other helium. The helium would be used to pressurize the hydrogen tank to feed the engine.

The first test was a failure

On the 23rd of December 1956, former Navy pilot William V. Gough Jr. was at the controls with Joseph S. Algranti occupying the Canberra's rear seat from where he would operate the special controls of the hydrogen fuel system. To ensure the safety of people on the ground in case anything was to go wrong, it was decided that the test would take place while flying over Lake Erie.

Once the aircraft had reached an altitude of 50,000ft, they switched from Jet fuel to hydrogen. Immediately, the engine started overspeeding and heavily vibrating. The pilots quickly shut down the engine and returned to Cleveland on one engine.

Stay informed: Sign up for our daily and weekly aviation news digests.

The third test flight was successful

The transition from jet fuel to hydrogen was successful on the second test flight. Still, an insufficient hydrogen flow to the engine prevented the engine from performing high-speed operations. On February 13, 1957, a third test flight saw everything go to plan with the engine running on hydrogen for 20 minutes. The pilots said the engine responded well to throttle changes and were pleased by how it performed.

Not only did the B-57 test flights prove that hydrogen could power jet engines, more importantly, it also proved that the cryogenic fluid could be safely stored and pumped in an operational system. Despite the project's success, the tests ended as the Air Force no longer needed aircraft to fly at such a high altitude.