Back in the early 1970s, Sydney-Kingsford Smith Airport was almost the site of Australia’s own Tenerife air disaster. Almost. A misunderstanding in communications from air traffic control saw a very near miss between a departing Boeing 727 flown by Trans Australia Airlines, and a CP Air Douglas DC-8. Everyone survived, and nobody was hurt, but the damage to both aircraft was extensive.

An average night in Sydney

The evening of January 29th, 1971 was dark and wet at Sydney-Kingsford Smith Airport. VH-TJA, a Boeing 727 operated by Trans Australia Airlines, was ready to depart for Perth. It was loaded with 84 passengers and eight crew members, and called in to surface movement control for clearance to taxi to the runway. At just before 21:30, it was given instructions to hold on a taxiway for Runway 16.

Seconds later, a Douglas DC-8 flown by Canadian Pacific and operated as CP Air, radioed the tower to advise they were on approach to Runway 16. CF-CPQ had 136 passengers and 12 crew members onboard. Given the dark, wet evening, it was undertaking an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach to the airport.

As the Trans Australia 727 arrived at its holding point, it radioed in that it was ready to take off. The controller advised that CF-CPQ was on short finals, and to line up on the runway once it had landed. The CP Air DC-8 landed safely, observed by the Trans Australia pilots, who taxied the 727 into position for a takeoff roll.

Communication problems

It was at this point that a simple misunderstanding of an instruction from the controller almost led to a major disaster. The DC-8, nearing the end of its landing run, received from the controller the instruction to “…take taxiway right, call on 121.7”. However, what the crew heard was “…backtrack if you like, change to 121.7”.

The crew proceeded to turn the aircraft around on the runway and taxi back the way they had come, directly towards the 727. The DC-8 involved in this incident was not just any DC-8, but precisely a DC-8-63, a stretched version sometimes known as a ‘Super DC-8”. This aircraft's long, heavy construction meant that taxiing maneuvers had to be carried out at low speeds and with great care.

Stay informed: Sign up for our daily and weekly aviation news digests.

Given the wet runway surface, the CP Air crew proceeded to turn the aircraft very slowly around, in a spot that was adjacent to Taxiway I. The controller saw the aircraft turn towards the taxiway and believed it would be heading off the runway along that exit. Subsequently, he went ahead and cleared VH-TJA for takeoff.

As per instructions, the CP Air crew had changed to frequency 121.7 as they commenced the turn. Therefore, they would not have heard the clearance for takeoff issued to the 727. Although the DC-8 reportedly had all its landing lights illuminated, as well as its wing floodlights and rotating anti-collision beacons, the Trans Australia crew did not see the aircraft at the other end of the runway.

The airline industry is always full of new developments! What aviation news will you check out next?

A very near miss

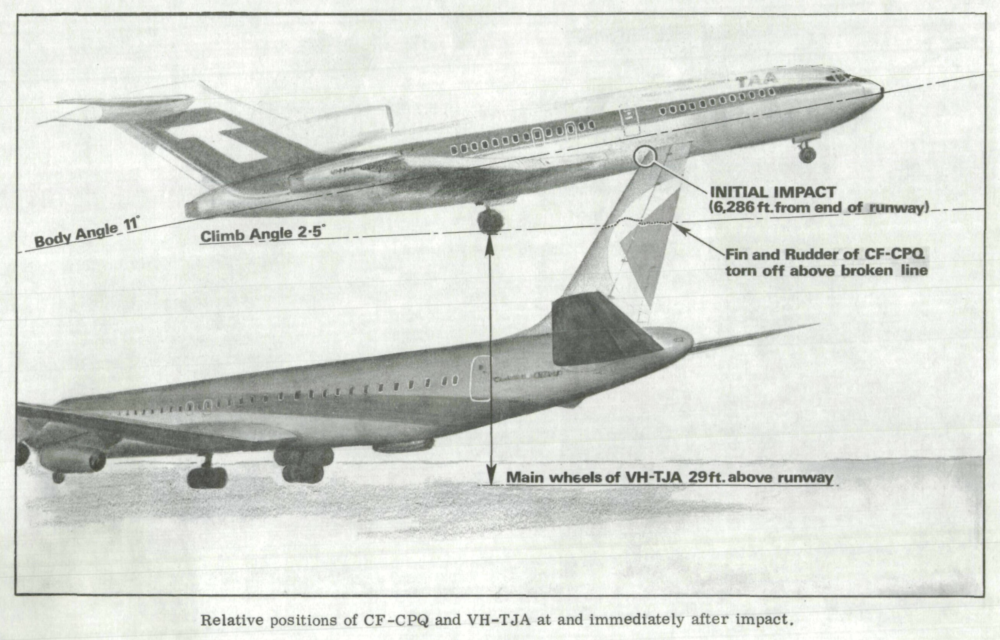

The Boeing 727 had begun its takeoff roll without noticing the DC-8. The crew reported that they didn’t spot the other aircraft until they had already reached V1, the speed at which takeoff must continue (131 knots in this instance).

At this point, the captain saw the DC-8 but judged it to be too late to abandon the takeoff. He concentrated on performing a normal takeoff technique, focused on avoiding a panicked over-rotation and hoping to pass above the DC-8.

In the CP Air cockpit, the captain had begun the backtrack down the runway, but then noticed that the aircraft he had seen holding at the other end of the strip was moving. Realizing it was in the throes of a takeoff roll, he steered the DC-8 towards the eastern side of the runway. However, despite these efforts, it was too late.

The approaching aircraft was observed to rotate and lift off, flying over the top of CF-CPQ. The captain of the CP Air aircraft noted a bump or a jolt, but assumed it was his nosewheel entering a depression off the edge of the runway. Unfortunately for both aircraft, it was not. Instead, the two jets had made contact with each other.

Specifically, the 727 had struck the tail of the DC-8 as it lifted off. The tail of the CP Air aircraft was substantially damaged, as was the underside of the 727. Trans Australia reported straight away that they believed they had struck the DC-8 as they lifted off, and reported that they had lost hydraulic pressure in their A system. The 727 dumped fuel offshore and safely returned to the airport.

A lengthy investigation

Australia’s Air Safety Investigation Branch investigated the incident. Otherwise known as the ASIB, this department was later rolled into the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB). The investigation took around six months to conclude. The cause of the accident was determined to be as follows:

"The cause of this accident was that the taxying clearance given after landing was misread by the flight crew of CF-CPQ and this error was not detected by the aerodrome controller, who cleared VH-TJA for take-off. The flight crew of VH-TJA, on detecting the obstructing aircraft, did not then adopt the most effective means of avoiding a collision."

Incredibly, both aircraft were repaired and went on to fly for many more years. VH-TJA ended up with Air Florida as N40AF, and later as N18480 with Continental. It was eventually scrapped in 1991, 20 years after this incident. CF-CPQ went on to fly for Worldways Canada from 1983 to 1991, when it was converted to cargo for Airborne Express. It was finally withdrawn from use in June 2002.

Not the only Australian tail-loss incident

As it happens, the CP Air DC-8 is not the only aircraft to have lost part of its tail in the context of a flight to Sydney. Indeed, a similar fate befell a British Airways Concorde in 1989, when part of the upper rudder fell off during a flight from Christchurch, New Zealand. Simple Flying explored this incident in detail in 2020.

What do you make of this near miss? Do you know of any other similar stories? Let us know your thoughts in the comments.