On September 13th, 1992, a Douglas DC-10-30 was scheduled to fly a charter service to JFK Airport in New York from Madrid. The flight, operated by Spantax, was to make an intermediate stop in Malaga. It arrived from Madrid at 08:20 local time, with 121 passengers, one baby, 13 crewmembers and four airline employees on board.At Malaga Airport, a further 251 passengers were embarked, and the plane was cleared for takeoff at just before 10:00. It proceeded to begin its takeoff roll as normal, and all was well, to begin with.

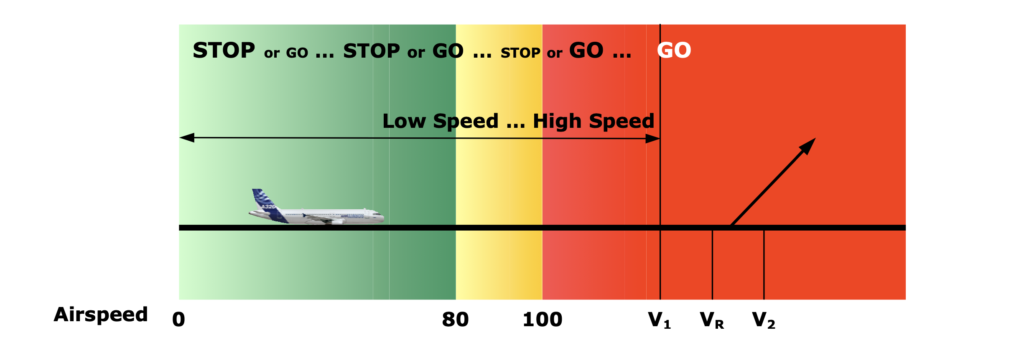

However, as the aircraft approached V1 – the decision speed beyond which a rejected takeoff should not be performed – the flight crew noticed a strong vibration. Noting that the power from the engines was unaffected, the captain decided to continue rotation.

As the nose gear lifted off the runway, the vibration became much worse. The captain, fearing the aircraft would be uncontrollable once in the air, called a rejected takeoff at somewhere between VR (rotation speed) and V2 (the takeoff safety speed). With only 1,295 meters, or 4,250 feet, of runway left, the DC-10 failed to stop before the end of the runway.

Damage to the aircraft

As the aircraft left the runway, it was still moving at approximately 110 knots (127 mph / 204 kph). It collided with an ILS concrete building, causing engine number three to detach from the plane. It smashed through a metal fence around the airport perimeter, and continued to cross a highway, damaging three cars in the process. Still it didn’t stop.

It finally collided with a farm building, coming to rest approximately 450 meters (1,475 feet) from the end of the runway. Some three quarters of the right wing as well as the right horizontal stabilizer detached on impact, and the fuselage scraped along the farm building, damaging the underside.

At the point at which the aircraft came to a stop, there was no damage to the cockpit or passenger cabin that would impede the survival of the people on board. But the damage to the wing proved to be the fatal blow.

Devastating fire

Loaded with fuel for the onward journey, the damaged wing began to spill fuel around the plane. A fire broke out in the rear of the fuselage, quickly spreading through the plane. It was this that caused the deaths of 50 people – 47 passengers and three crewmembers. The fire engulfed the plane and destroyed it completely.

One person was badly hurt from the impact of the plane with vehicles on the highway – a driver of a delivery truck. A further 110 people suffered injuries, mostly as a consequence of the fire or from smoke inhalation, while some were hurt during the slide evacuation.

After the crash, most of the uninjured survivors were taken to New York on a special flight organized by Iberia. Several dozen, however, refused to continue their journey due to the shock of the accident.

The cause of the accident

Subsequent investigations showed a failed tire was the cause of the vibrations. The tire on the nose gear, placed in position 2, had begun to disintegrate, causing a rumble that was hard for the flight crew to identify.

Ultimately, the tire remains were studied in great detail, and it was found that there was a flaw in the retreading process. The tire had been retreaded three times prior to this flight – a perfectly normal process in aviation, but an issue with the process on its last retreading caused the rubber to delaminate and begin to separate from the tire as the aircraft reached almost V1.

Human factors

However, there were human factors in this disaster that contributed to the outcome of the rejected takeoff. The airplane had passed V1, which is the decision speed, after which a rejected takeoff can risk a runway overshoot. At the point of reaching V1, the captain moves his hand from the power control to the control column, indicating that rotation will occur, no matter what.

In this situation, it meant the sudden decision to stop rotation saw the captain rapidly moving his hand back from the control column to the throttles, to shut it down. But as he was trying to throttle back and turn on the reverse power, the engine number 3 throttle lever slipped from his hand. This asymmetry of power caused the airplane to deflect to the left, and the spoilers failed to deploy as the reverse cycle had not been completed.

The captain was trained to call an aborted takeoff due to engine failure, but had no understanding of what was causing the vibration. He had begun to rotate the aircraft, but noted that the vibration became worse as the nosewheel lifted off the ground. This caused a moment of panic, that ultimately led to a rejected takeoff being called much too late.

There were problems with evacuation also. The airplane had lost power, so the captain could not call through for evacuation. The DC-10 also did not have an evacuation warning system fitted, as it was not required in those days, and cabin crew could not get to the loudspeaker system to announce the evacuation. Various doors on the right-hand side were unable to be used for evacuation due to the fire, and progress was noted to be slow in the forward cabins as passengers stopped to collect their hand luggage before disembarking.

Learning from mistakes

As a consequence of this disaster, pilots are now trained on failures other than that of engines, particularly relating to problems with the landing gear. Retreaded tires are now strictly regulated, and cabin crew are trained to demand compliance with the hand luggage rules in the event of an evacuation.

Additionally, loudspeakers and other articles designed for evacuation are now placed within easy reach of the cabin crew seats, and buildings and other constructions in the area of an airport’s runway are designed to be more frangible.