When you step onto an aircraft about to embark on a flight with a commercial airline today, in any part of the world, chances are it will either be a Boeing or Airbus jet. Earlier players in the commercial jet manufacturing arena have bowed out, and left standing are two aerospace giants that seem so unshakable in their duopoly it is easy to forget things were ever different. Or indeed, to imagine that it could be any way else in the future.So how come there are no real competitors to Boeing and Airbus when it comes to commercial aircraft? Of course, China's COMAC is making a play at some domestic market share with the C919. Sanction-riddled Russia also hopes to produce 1,000 homegrown jets by 2030, but this pretty much pales in comparison to the over 7,000 aircraft in Airbus' backlog at the end of 2022, or for that matter Boeing's at just over 4,500 units.

Embraer does well in the regional jet segment, which occupies 13% of the global aircraft market. Furthermore, turboprops are an area to themselves, taking up 9%. However, narrowbody and widebody jets make up 60% and 19% of the global fleet, respectively, and here Boeing and Airbus reign supreme. So what are the key factors that make them so superior?

How to build your own commercial aircraft

Essentially, it's down to the various factors that go into building and operating commercial aircraft. Here is a brief, but not comprehensive, list of different factors that go into the high barrier to entry into the aircraft manufacturing market and that the two companies have spent decades developing.

- Expertise. All of these aircraft designs and their variants have been created from the ground up or over years of research and development. For instance, the A320 was first announced in 1981 and only took off on its maiden flight in 1987. Meanwhile, the 777X variant of Boeing's popular widebody was launched in 2013 but did not fly until 2020 (and has yet to enter service). Airbus and Boeing both invest heavily in R&D and continuous development, but even with substantial coffers to pull from, things do not always go according to plan.

- Funding. Because it takes several years, if not decades, to create an aircraft, new manufacturers would need plenty of funding before they can even begin contemplating selling the plane to operators. The large players in the industry, Airbus and Boeing, have a proven track record of delivering planes that airlines trust. As a newcomer to the industry, it is almost impossible to get a presale without the jet already existing (although the eVTOL market seems to be an exception to this rule).

- Government lobbying. In the perfect marketplace, all companies would be able to compete for the same customers. However, when one company employs thousands of people in specific locations in a country, it can actually lobby the government to take action against new competitors. As seen with Boeing vs Bombardier (see below), firms would also need to find a way to be able to sell the jets they are building.

- Manufacturing. Just like you need money and expertise to design the aircraft, you also will need a billion-dollar production facility and staff who know how to build them. Unlike other businesses, you can't just get your jets made elsewhere as it's such a specific industry. With this comes issues with establishing supply chains, where Boeing and Airbus have established long-lasting partnerships.

- Regulatory approval. Aviation is the safest mode of transportation available today, and certification of new aircraft is a rigorous process. Having the experience of having gone through the procedure repeatedly is certainly an asset; something startups do not possess.

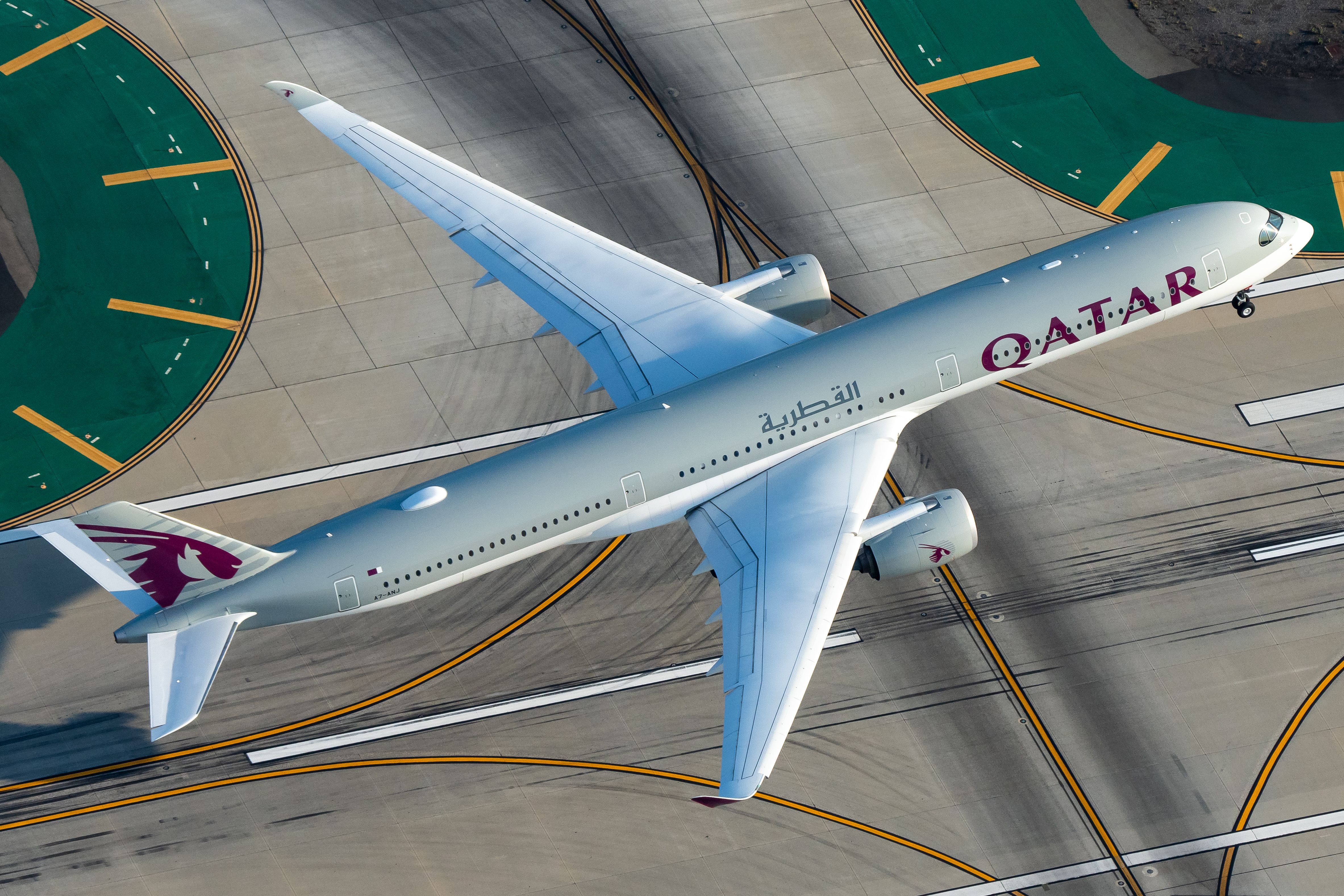

- Aftermarket service and other issues. Manufacturers do not just build and sell the planes, and then that's it. Various problems could occur that they could be held accountable for, or at the very least, shell out a significant amount of money on legal fees to deal with sources of contention, such as the s(somewhat surprisingly) amicably settled argument between Airbus and Qatar Airways over the A350, or, the horrible scenario of two 737 MAX jets crashing and causing the deaths of hundreds of people.

Furthermore, Airbus and Boeing both have the economy of scale on their side. With multiple production facilities, they are able to produce large quantities of aircraft, which lowers their per-unit production cost. This has allowed them to maintain competitive pricing and increase market share over time, seeing the two compete neck-in-neck with each other over the past decade.

The smaller players

So what is going on with the other companies making planes in the shadow of the two big guns?

Bombardier

Canadian Bombardier, makes small to medium jets in the marketplace. However, they overreached with its CSeries, which was seen as a serious rival to smaller Boeing and Airbus jets, as the development costs soared to $2 billion above budget.

When it came to selling its CSeries to the world, Boeing slapped an embargo via the US government (thanks to aforementioned lobbying) and had the sale banned. It took selling 50% of the company to Airbus to get the embargo lifted, but at this point, the CSeries became the Airbus A220.

Get the latest aviation news straight to your inbox: Sign up for our newsletters today.

Embraer

As with many successful smaller companies, the Brazilian jet maker was almost scooped up by a larger competitor, namely Boeing. The American aerospace giant wanted to buy Embraer, much as a response to the Airbus/Bombardier affair, but the Brazilian government vetoed the sale as the company also made military jets for the South American nation.

The two did strike up a partnership agreement for a joint venture to sell Embraer commercial jets under the Boeing name. However, things ended on a sour note when Boeing pulled out of the $4.2 billion deal which would have seen it acquire an 80% stake in Embraer's commercial jet division. The joint venture deal was terminated in April 2020, as Boeing found itself dealing with both the lengthy grounding of the 737 MAX and the fallout of the pandemic.

COMAC

Recent years have seen China's aircraft manufacturing gather speed, with the C919 narrowbody selling well domestically with over 1,200 orders. The jet seats 174 passengers in a single-class configuration, around the same as the Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX-8, and China is planning to produce around 150 jets per year in five years' time, Reuters reported in January. Furthermore, it also has a regional jet, the ARJ21, seating up to 90 people.

COMAC also has a widebody project together with Russia, the CRAIC CR929, which is planned as a competitor to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner. The project has hit several snags on the way, and although it has reportedly entered the initial design phase, it is unclear when mass production could get underway.

Irkut

Speaking of Russia, we cannot fail to mention the MC-21, which despite the substantial hiccups, now looks to be a commercial success if nothing else than for the fact that Boeing and Airbus aircraft are off the table for Russian carriers, who will be needing new planes before long. The narrowbody will now only be available in an "import-substituted" version, designated the MC-21-310. Well, that is one way of dealing with the duopoly, we suppose.

Source: Reuters